The recent announcement that the Ministry of Commerce is pursuing 20 billion baht in allegedly ‘fake’ rice deals in terms of compensation from six senior individuals, namely former commerce minister Boonsong Teriyapirom; his former deputy Poom Sarapol; Manas Soyploy, a former director-general of the Department of Foreign Trade; his former deputy Tikamporn Natvorathat; and Akrapong Theepvajara, ex-director of the Foreign Rice Trading Office, makes one wonder how deep the rabbit hole goes. The Corruption Perceptions Index 2016, produced by respected international NGO Transparency International, helps provide part of the answer, if not already evident – all the way to Wonderland, of course.

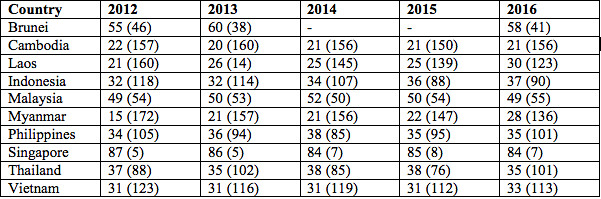

First launched in 1995, the CPI is probably the world’s leading assessment of corruption, is compiled by businesspeople, analysts, and experts, and is widely referenced in academic literature, in the media, and by civil society. Here is a handy tabular breakdown of the last five years for ASEAN countries:

Score (Ranking) for 2016 (/ 177)

Singapore is the only ASEAN country rated as Very Clean. Brunei remained above the 50 points mark, with Malaysia back to where it was in 2012. Indonesia, Thailand, and the Philippines are all muddling along being ‘corrupt’, in the same bracket as Cambodia and Myanmar, the latter of which was ‘very corrupt’ only five years ago. As Transparency International points out, in corrupt and very corrupt countries, “people frequently face situations of bribery and extortion, rely on basic services that have been undermined by the misappropriation of funds, and confront official indifference when seeking redress from authorities that are on the take.” The 20 billion baht of ‘fake’ rice rings a bell here.

Looking at individual countries moving up the rankings, Indonesia is clearly, if slowly, improving, following years of dictatorship and military rule. Laos is also slowly showing signs of improvement as the communist government realizes that some kind of legal framework generates inwards business and donor investment, which benefits those at the top most, i.e., the communist government and their business interests. This is essentially the same realization that the rulers of Myanmar came to, following years of slowly increasing Western inwards investment, and Myanmar has now overtaken Cambodia and is no longer the most corrupt country in ASEAN, even posing a challenge to Laos.

Cambodia’s low score and associated abysmal ranking are attributed to its utter lack of room for civil society or of any effective judiciary or rule of law and thus the absence of a public sphere. In the case of Myanmar, the National League for Democracy, which came to power after elections in March 2016, has basically declared a war on corruption in a measure supported by some unelected military members of the Pyithu Hluttaw national assembly, which is fine in principle. However, the challenge will be what happens when corruption is detected in high-ranking officials in the Tatmadaw, the Myanmar Armed Forces. Moreover, the impunity of the Tatmadaw was demonstrated in its crackdown on the Rakhine State Muslims, and wanton, unchecked acts of majority-on-minority inter-ethnic violence do not inspire confidence in the transparency of a government.

Both Malaysia and the Philippines are essentially treading water. TI points out that while Duterte has promised a war on corruption, in actuality his government has instituted arbitrary rule, with personal attacks on the media, violent intimidation, and death squads undermining democratic rule. In Malaysia, the main focus is on Prime Minister Najib Razak, with the allegation of USD 700 million somehow arriving in his personal bank account from state-owned investment firm 1Malaysia Development Berhad casting a pall over the integrity of the entire country.

Thailand is down this year, equal to the Philippines, and only two points ahead of Vietnam, one of Thailand’s closest competitors for inwards foreign investment. Thailand’s falling score is attributed by TI to the political turmoil, specifically Cambodian-style political repression and the lack of any independent oversight, with a resulting deterioration of human rights. The collapse of a human rights framework is indicated by the downgrading of Thailand’s National Human Rights Commission and is being accompanied by the slow death of civil society, according to the latest Human Rights Watch 2017: Thailand report, broken down here by Special Circumstances. The lack of any independent oversight or even-handedness in the referendum process for the constitution are stressed by TI as contributing to the lower score. TI points out another contributing factor is that the constitution entrenches military rule, a reference to Myanmar-style embedding of military picks in the Senate, which potentially builds in unaccountable corruption in the next government.

This year’s CPI results have been used by TI to highlight the connection between corruption and inequality. As José Ugaz, Chair of TI, puts it, “In too many countries, people are deprived of their most basic needs and go to bed hungry every night because of corruption, while the powerful and corrupt enjoy lavish lifestyles with impunity.” TI stresses that a lack of action in addressing corruption leads to populism because of the vicious cycle of corruption, unequal distribution of power, and unequal distribution of wealth.

When citizens see public money being squandered, for example on rice subsidies, they see public funds being diverted to serve the rich, through kickbacks, and they do not feel they can change the system. If citizens do not believe the state can address such issues itself, they believe the situation is rigged, which leads to popular disenchantment. This leads to citizens supporting populist candidates, or in the case of Thailand, a middle-class-supported military coup. However, the Thai military is equally adept at squandering public funds and amassing wealth, via expenditures on Chinese main battle tanks and submarines, or coal-fired power station mega-projects, or just on perpetuating an inefficient education system. Moreover, it has done little to substantially re-distribute wealth or power in Thai society, with only token nods to inheritance and land and property taxes.

To address systematic corruption, TI recommends breaking the linkages between business and high-ranking government positions, holding corrupt officials to account instead of allowing impunity, enforcing greater controls on money laundering, and outlawing the use of secret companies, a reference to shell companies, such as those with offshore accounts. The junta is certainly making a lot of noise about taking such measures with the announcement regarding the fake rice deals. However, whether entrenched interests like the Thai military itself will permit these guidelines to be applied to them under the next, hopefully democratic, government, will likely rely on the extent to which a responsible, principled government is elected. The task will be for that government to openly discuss societal corruption, including military impunity, with the military. Thailand’s position as fifth equal in the CPI rankings for ASEAN should spur such a dialogue.

Prachatai English is an independent, non-profit news outlet committed to covering underreported issues in Thailand, especially about democratization and human rights, despite pressure from the authorities. Your support will ensure that we stay a professional media source and be able to meet the challenges and deliver in-depth reporting.

• Simple steps to support Prachatai English

1. Bank transfer to account “โครงการหนังสือพิมพ์อินเทอร์เน็ต ประชาไท” or “Prachatai Online Newspaper” 091-0-21689-4, Krungthai Bank

2. Or, Transfer money via Paypal, to e-mail address: [email protected], please leave a comment on the transaction as “For Prachatai English”