Before the intensification of Southern Thailand’s long-running insurgency in the early 2000s, the region, (known as Patani) lacked a developed art scene, and the conflict which erupted in 2004 seemed to have devastated artistic creation among the local population. However, in the middle of the endless armed conflict, a new generation of artists has emerged in the region, struggling to seek out their identity/the region’s real identity through the creation of artwork.

I was born in Tokyo and grew up there. I didn’t think of the city around me as being particularly rich in culture – it’s not an old city with historical sites like Kyoto. The place where I was born and lived for more than 20 years, a district called Suginami, is located less than 15 kilometres (or five railway stations) away from Shinjuku Station, the busiest station in the world with more than 3 million travellers passing through each day. Yet Suginami used to be a farming village and was developed relatively recently, only after World War II. Only 40 years ago, it still bore the remnants of farmland with lots of vacant spaces and plenty of public parks. It wasn't difficult to find a playground. The region had an intangible scent of culture, probably because of the many writers, scholars, and artists who dwelt in the region. However, the main function of my district was as a place to live. Most cultural activities took place in busier, more central districts.

I don't remember exactly when I began to visit museums and galleries on my own. Certainly, the first visit would’ve been a school trip. On a school trip to a national museum in Tokyo, seeing the originals of works I had come across before in pictures, I was obviously more excited than most other students. The atmosphere of serenity in the museum was exactly what I loved. By the time I was a university student, visiting museums and galleries had become a favourite pastime of mine. I wasn’t sure if I really enjoyed appreciating the pieces exhibited. The real purpose might be the talk I had with someone (sometimes a girl!) after the visit to the exhibition we had just attended. This is something I really missed when I came to Southeast Asia.

The first place I stayed in the region was Kuala Lumpur. I stayed on the campus of the University of Malaya, where I finished my master’s degree. It was near the end of the last century, 1998. Malaysia is an interesting country in many aspects. While I was there, the capital of the country was just beginning to drastically transform itself into the modern city we see today. It still had the remnants of the old town’s character, the city itself was charming. However, I found the museums were really disappointing. I had imagined that every capital of a country must have a lot of good museums where you could spend hours without getting bored. I was naïve. To be fair, it didn’t mean that Kuala Lumpur didn't have any cultural activities, only that these things were not presented as they were in my own city. And, at that time, Malaysia was going through a period of rapid economic growth. It was highly likely that the government gave little attention to things like art, which didn't help GDP growth (at least in a direct way). All in all, my life in Kuala Lumpur was enjoyable, but just one aspect was missing: regular museum and gallery visits.

The poster of an exhibition called ‘Patani Semasa' (Contemporary Patani). Source

In 1999, I moved to Pattani Province, Thailand, to conduct my research on the Patani dialect of Malay spoken in the region. I immediately fell in love with the place. The climate was moderate, the food was excellent, the town itself was cosily small and comfortably relaxed, and the local people were very amicable. Although there were very occasional bombings and school arsons, the armed conflict hadn't emerged yet. The only things I hated were mosquitoes. Nevertheless, regarding the artistic space, I must say I felt as if I was in a desert. Suddenly Kuala Lumpur looked like a very sophisticated place. In Pattani, there was neither a good museum nor a good gallery. The only type of drawing you could easily find were the mass-produced fake artworks based on touristic stereotypes (like a picture of a fisherman's boat on a sandy beach under an unnaturally blue sky with artificially well-shaped coconut trees) sold in souvenir shops. I had to tell myself, ‘well, this is a poor, provincial town in a developing Southeast Asian country. You can enjoy museums and galleries when you go back to Japan'. Appreciation of artworks was still a missing part of my life. This was my perception until quite recently.

However, over the last few years some changes have gradually become visible. An art gallery was opened near the Big C shopping centre (which was bombed on 9 May 2017) by a lecturer of the Faculty of Fine Arts, Prince of Songkla University, Pattani Campus. Later, the gallery was moved to a new exhibition centre called ‘Patani Art Space' located just outside the town. It's now regularly visited by curators, collectors, researchers, diplomats and students. Another local artist opened a café in the town, exhibiting his works. The artwork by the local artists, including the owner of the art space, has also gained recognition from outside the area. In July 2017, the

Maiiam Museum in Chiang Mai hosted an exhibition called ‘Patani Semasa' (Contemporary Patani). Later the artists involved were named as among the "outstanding Thai artists in 2017" by the

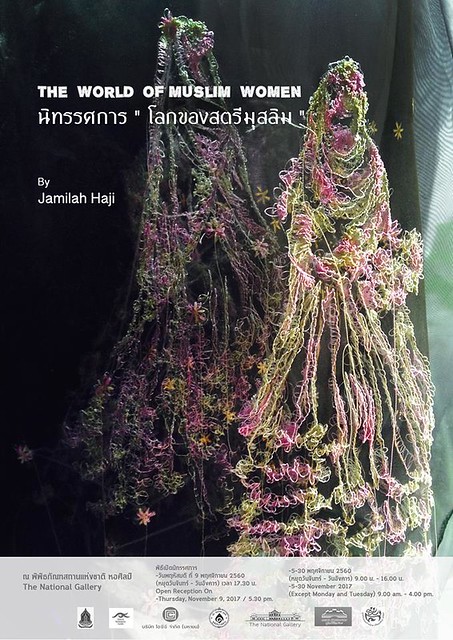

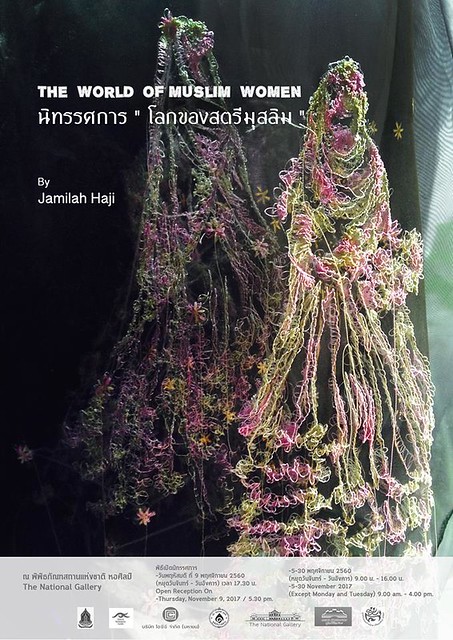

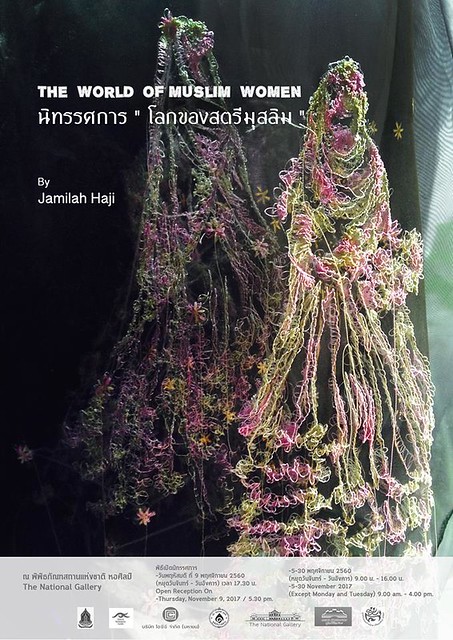

Bangkok Post. In November 2017, a local female artist had an exhibition called ‘

The World of Muslim Women' in the National Gallery in Bangkok. In December 2016, a group of young writers, led by Zakariya Amatya, a SEA Write Award-winning poet, published a book (written in Thai) called

The Melayu Review.

The poster of an exhibition ‘The World of Muslim Women' in the National Gallery in Bangkok.

Source

Rather belatedly, I began to realise that my perception of Patani as an artistic desert must be wrong. How else could one explain these remarkable recent developments? How was this development possible?

I used to presume that the current conflict, particularly severe since 2004, which has claimed more than 6,000 lives, must have devastated peoples' creative lives.

I couldn't imagine what it was like to grow up in the middle of the conflict. I naively imagined that it must have eliminated any kind of positive aspects from our live including the thirst for artistic creation. I was completely wrong. Something was burgeoning under the surface of the desert. It was invisible to me, and probably for many who had been overwhelmed by the conflict. Art survived and is now beginning to blossoming in Patani, right in the middle of the bloody conflict.

This is probably part of a bigger change currently happening in this region. It's not only visual art. Photographers in the area used to only take pictures of wedding ceremonies, graduation days and family pictures for purely commercial purposes. Now, a group of young local photographers seek out that which is photogenic. Some of them have picked up the camera to capture video clips, and some have produced short films. A completely new kind of coffee shop is appearing in the region, ones that function as temporary or permanent galleries. These cafes are designed by local architects too. Local young singers are singing their own songs, composed by themselves, not merely copying popular bands from Bangkok. All these new developments have begun in the past few years, probably no more than five years. At first, I cynically thought it was a temporary fad, backed up by the spreading use of social media, and funded by international organisations which are always so eager to present something positive from the conflict area. I was, to my delight, wrong too. These are new currents which started in the middle of the conflict and are propelled by those who grew up in a place known for bombings and shootings. They begin to seek the meaning of their existence via the form of ‘art'.

We haven't got a museum as we have in Tokyo or Bangkok yet, but in Patani art is vibrantly alive. Being in touch with these forms of art is, at least, no less exciting than visiting a good museum. This series of articles will relate the stories behind this current development, first by focusing on visual art.