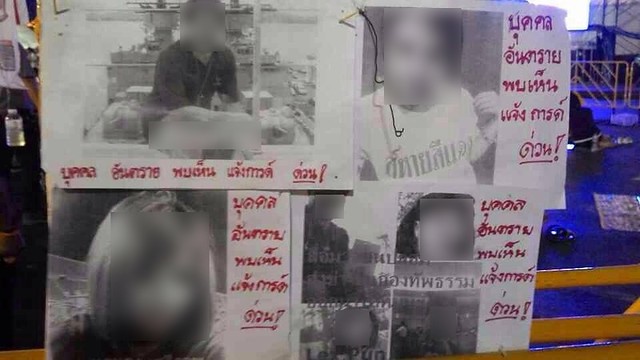

A picture taken at a People’s Democratic Reform Committee (PDRC) rally shows four red-shirt activists. Nok is at the bottom left. The text reads “Dangerous persons. Notify the guards when you see them.”

Nok is an active anti-establishment red-shirt supporter from Bangkok. She and her red-shirt network often organized political activities, such as a small seminar on the rights of political prisoners. When the People’s Democratic Reform Committee (PDRC) a few weeks ago marched near her place, she took a photo with the rally as the background and posted it publicly on her Facebook page, which has more than 5,000 “friends”.

A few days later her photo appeared, along with three other red shirts, at the gates of the rally. The sign says “Dangerous persons. Notify the guards when you see them.”

There are also online campaigns against her, accusing her and the other three of trying to spy on the PDRC by disguising themselves as PDRC supporters and joining the rally.

Nok insisted she has never gone to a rally.

Because of the online and offline campaign against her, and because a current PDRC rally site is not far from her apartment, she decided to move out temporarily to stay with a friend in another area. Her colleague also threatened her, saying that she “had better stay at home” otherwise she will disclose her location to the PDRC guards, Nok said, adding that she then decided to resign.

A picture taken at a People’s Democratic Reform Committee (PDRC) rally shows a PDRC supporter holding a sheaf of papers for distribution. The document shows (from left) Eakaphob L, a red-shirt supporter, Somsak Jeamteerasakul, Thammasat University historian, Jai Ungpakorn, a former Chulalongkorn University political scientist, and Saran Chuchai, aka "Aum Neko", Thammasat student. All of them are subject to lèse majesté charges. The text above the photos says “Think differently, and I don’t care. But you have insulted my royal father, and I won’t take it.”

Unlike the Arab spring where cyberspace was credited with a prominent role in the revolutions for democracy, Thailand’s cyberspace has been used extensively to call for less democracy and less freedom of expression.

Thai cyberspace has been overwhelmed with political cyber-bullying, or intimidation and harassment of someone because of their political views, especially on issues related to the monarchy.

The first recorded case of this form of harassment was in early 2010, when tension between pro-establishment and anti-establishment groups escalated during to the red-shirt demonstrations which ended with a military crackdown on red-shirt supporters in Bangkok in which 92 people were killed. Many red-shirt supporters expressed their anger in reckless comments about the monarchy on Facebook.

Vongvipa K., a red-shirt supporter in her 30s, wrote several Facebook comments that satirized the monarchy, such as a complaint about an anticipated intervention that might have been able to stop the crackdown. Another comment was “I respect only my own biological father.”

These comments were widely shared until it caught the attention of some royalists who started a bullying campaign against her by forwarding messages.

The messages accused her of defaming the King and included screen captures of the problematic Facebook comments, photos of her and personal information such as name, date of birth, address, and, more importantly, her employer’s phone number. It identified her as working for a foreign delivery company. Her case was later published on several royalists’ blogs.

“It is unbelievable that a person who calls herself “Thai” is bold enough to do this,” wrote one comment on a blog post that condemned her.

A few weeks later, more forwarded messages appeared saying that someone had called her employer to complain about Vongvipa’s “disloyal” behaviour. A letter with the company logo later appeared and was circulated, stating that the company had fired her.

The writer failed to contact Vongvipa for an interview.

In another appalling case, mainstream media were instrumental in victimizing a girl then 18 years old.

Screenshot of a YouTube video bullying Kanthoop.

Kanthoop (joss stick) was the pseudonym used by an adolescent to express her political opinions on the hardcore anti-establishment Same Sky web forum around five years ago. She currently is a 21-year-old university student. In early 2010, when she was a 12th grader, she created a Facebook account under her real name and posted a bold criticism on the establishment. A few months later, threatening messages were distributed, containing captures of her Facebook status, photos and personal information, accusing her of insulting the King. Several Youtube videos were also threatened her.

The messages were later disseminated on other platforms such as blogs and web forums and she started to face offline harassment. She passed the entrance examination to four state universities in Bangkok. After this news spread, there were campaigns against her both online and offline which pressured the universities not to admit her.

Facebook pages were created by members of these universities, specifically campaigning against her. “We, XXX University, don’t want [Kanthoop’s real name],” is an example of the title of one such page.

A protest against her, initiated and organized on Facebook, was held at one university on the day of her interview. She decided to abandon the interview for her own safety. In December 2010, she was admitted to Thammasat University’s Faculty of Social Work, where she has been bullied by fellow students and lecturers since the very first day of classes.

Members of pro-establishment Facebook pages who engaged in cyber-bullying against her have also filed lèse majesté charges against her on several counts. She faces a potential jail term of up to 50 years. The case is now under investigation and she has to report to the police from time to time.

Asked if she could go back in time, would she still post those messages, Kanthoop answers, “I would still do the same. I think that my life has had lots of problems, but today it is ok. I'm happy. The people who were in [the SS] have their own ideologies. There is nothing to stop them if they don't stop themselves.”

Social Sanction Group: Organizing political cyber-bullying and witch hunts

Around the middle of 2010, bullying became more organized when a group called Social Sanction (SS) was founded. Run anonymously, the group’s main objective was to ‘sanction bad guys’. It was founded on Facebook and gained popularity. SS was arguably the thing that made cyber-bullying widely known among Thai Facebook users and intensified the impact of bullying. By around July 2013, the page had more than 35,000 ‘Likes’.

Screenshot of the Social Sanction page captured in June 2013

A co-founder of SS, whose name is withheld due to safety concerns and is referred to here as ‘Mana’, told this writer that the group was founded because they believed that Thailand was sinking into an abyss as the result of corrupt politicians and they had no faith in the police or any established social institution except the monarchy.

Consisting of people who love the king and are against former premier Thaksin Shinawatra, the group believed that they had to help build a good society by themselves and SS activities were one way of fighting evil and creating goodness. Since all members were royalists, the ‘sanction’ of individuals who expressed comments critical of the King was inevitable and became the main task of the group, he said.

“I discussed with my friends how to deal with this as citizens when wrongdoers went unpunished. Someone suggested 'We must use social sanctions like other countries’. I thought, yeah, we must do it,” said Mana. “This method was used in the west.”

As they had no faith in the police, the group believed that “exposing” bad guys who posted defamatory messages about the monarchy would help bring the bad guys into the judicial system and expose them to the public. They also hoped that the bullying would create fear and prevent others from doing the same.

“We have to kill a chicken to show to a pack of monkeys,” he said, quoting a Thai proverb.

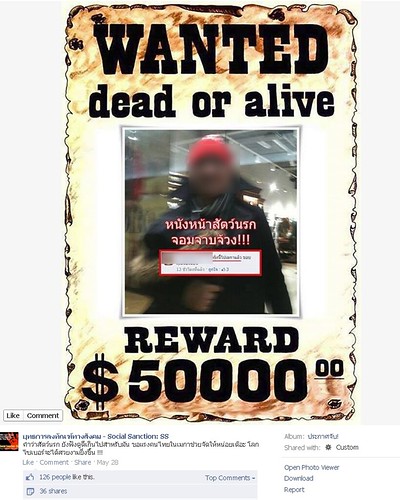

Bullying by the Social Sanction. Text in white in the middle says "The face of the evil from hell who likes to defame (the king)!"

In 2010 and 2011 the group was arguably ‘successful’ in creating a climate of fear in Thai internet circles.

The end of the SS came in July 2013 when the group launched a bullying campaign against the wrong person in a case unrelated to the monarchy. The mistake brought strong condemnation from Thai Facebook communities. The SS later closed down its page after they were threatened with a lawsuit and bombarded with photos of excrement.

Throughout the four years of SS’s existence, about 50 people were bullied.

Anti-Social Sanction: Fighting bullying with bullying

Anti-Social Sanction (Anti-SS) appeared in 2010. Run anonymously, the group tried to expose and bully people believed to be behind the SS group. (After the Anti-SS was frequently banned by Facebook, it changed its title to ‘Sanction Witch Doctors’ (SWD) in 2011.)

This writer interviewed Nithiwat Wanasiri and Surachat Singhaniyom, two of the core members of the Anti-SS.

Nithiwat, 26, currently a singer with the red-shirt

Faiyen band, was one of the first victims of the SS and a co-founder of the Anti-SS. He could be called an archenemy of the SS, given the frequency and the harshness of the bullying against him, which was one of the factors that made him well-known and seemed ironically to encourage him to defy the mainstream discourse about the monarchy by organizing and engaging in sensitive political activities.

Surachat is a 33-year-old businessman. After he was bullied by the SS, he kept a low profile, but on the underground, he turned into one of the core members of the Anti-SS.

“We would not allow ourselves to be hunted,” Said Surachat. “We had been harassed by phone calls and hate mail. I felt that if we also have arms and legs, we should hunt them back. Why should we let them attack us without retaliating?”

Surachat said the Anti-SS was composed of about ten members, all of them red-shirt sympathisers and some of them SS victims. They also tried to recruit SS victims as members.

Kanthoop was once approached by the Anti-SS group but declined the invitation. “I think [Anti-SS] is not the answer to this problem. If you don't like something, you should not do it,” said Kanthoop.

Surachat explained how they uncovered the SS team by first getting a tip-off from an SS-turned-red-shirt who acted as a double agent for the Anti-SS. They later launched a spy mission to identify SS members by creating more than 50 avatars to infiltrate the group of yellow-shirt pro-establishment online activists.

Throughout the two years of the Anti-SS’s existence, it bullied about 10 people who they believe were behind the SS or had closed links to it.

While in most cases, the SS only revealed information available from Google and Facebook, such as email addresses, affiliation, phone numbers and addresses, Anti-SS exposures were even more horrifying. They revealed, for example, the national identity and passport numbers of their victims and those of their parents.

Most of the Anti-SS’s victims, alleged SS members, were adolescents. Mana, the SS co-founder who this writer interviewed, declined to confirm the status of any of them.

Bullying by the Anti-Social Sanction. Text in white box is Facebook status of the victim saying "The red buffalos burned the town. You bustard. You will not die good."

Surachat said that apart from retaliation, they also wanted to create fear among SS members in the hope that the SS would stop bullying. However, it turned out that their activities fuelled the launching of a harsher SS campaign against red shirts as more red shirts were bullied at that time, Surachat observed. He added that the SS also tried to expose the Anti-SS team and successfully identified Nithiwat.

The Anti-SS decided to close down their page in December 2011 after the team realized that bullying cannot deter bullying, and, more importantly, an alleged SS group successfully pressured Kasetsart University to file a lèse majesté case against one of its students -- Nithiwat.

Bullying with False accounts to scare outspoken active yellows

Another tactic by an unknown ‘red’ group uses false accounts to shame lèse majesté supporters or scare outspoken or active yellows on Facebook by creating fake Facebook identities to express anti-monarchy views which are the opposite of their real stance, and so cause them to face intense hostility and possible lèse majesté accusations.

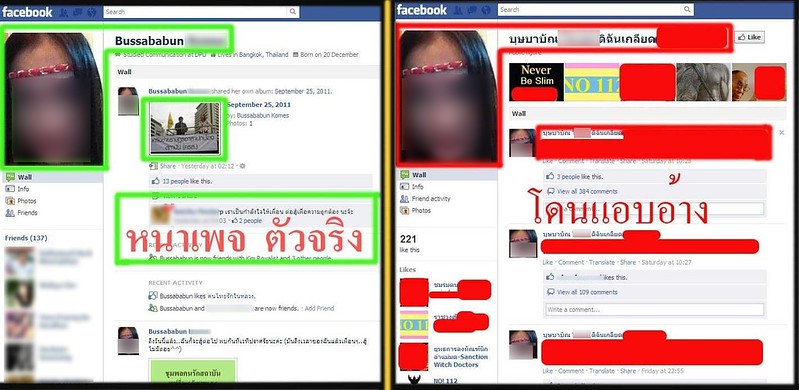

The photo on the left is a screenshot of the real Bussababun K.’s Facebook profile, while the photo on the right is a copycat account. Photo courtesy of T News

In 2011, Bussababun K. used her Facebook account under her real name to post several comments condemning an anti-monarchy Facebook page. As she was new to Facebook, she did not restrict access to most of her personal information. A day later, a Facebook age appeared called “Bussababun K. hates [the Kings name]” with profile photos similar to those used on Bussababun’s Facebook profile with similar personal information. The copycat page also posted photos and comments defaming the King.

The copy seemed to provoke opposition. She faced intense hostility from people who love the King. Later the following pages appeared condemning Bussababun:

- Confident that over 60 million Thais hate Bussababun K., an alien queer

- Against traitor Bussababun K.

- Confident that all Thais hate Bussababun K. I hate XXX

- Scold Bussababun K.

- Scumbag Bussababun K.

It is not clear whether these pages were created by royalists who wanted to condemn Bussababun or by the person behind the copycat page in order to stir up a tide of hatred against Bussababun.

According to T News, a pro-monarchy news agency, Bussabun said she did not create the copycat page and insisted that she loved the King. She also filed police complaints against the copycat page.

This writer failed to contact Bussababun for an interview.

The relation between political cyber-bullying and the lèse majesté law.

Although bullying has been done by both pro- and anti-establishment groups, the effect of bullying is more severe against anti-establishment groups because of Article 112 or the lèse majesté law.

For the SS group, Article 112 is the justification for bullying activities and also gives them leverage as they believe they are helping the state authorities to catch wrongdoers.

“Even if there is the law, it cannot be implemented,” said Mana. “Given a lame state mechanism, specifically in a police state . . . the police state would not enforce the law, hence, the law is not the law. What can the people do? . . . People must boycott and collaborate to impose social sanctions.”

Mana insisted that the state authorities were not involved with the SS.

The state authorities may not be directly involved with bullying activities, but it is noted that a few lèse majesté suspects have had charges brought against them because of online bullying.

There are four recorded cases where lèse majesté complaints/charges were brought after public attention because of online bullying. The four are Nithiwat, Eakaphob, Chanin K., and Kanthoop. The cases of Nithiwat, Eakaphob and Kanthoop are under investigation, while the case of Chanin is now before the Court of the First Instance. (Only Eakaphob was not bullied by the SS.)

The question arises: out of about 50 victims of bullying, why have only four been charged with lèse majesté?

The answer is that most Thais are aware of the taboo about talking about the monarchy and of the lèse majesté law. So most of Facebook comments that led to bullying were not really deemed lèse majesté, but may have been considered offensive by pro-establishment groups. Some comments merely criticise the lèse majesté law, the elite, “Thainess”, the Privy Council, and the Crown Property Bureau. Some criticisms refer to the monarchy using coded names. Sometimes the messages are heavily coded but still it can be interpreted as related to the monarchy.

“Sometimes an offence is not against the law. There are two cases: the first is not illegal but is immoral or goes against a tradition or a norm of our society; the second is totally illegal,” said Mana on the offences that he sees should be sanctioned.

In conclusion, political cyber-bullying is a new culture linked to the intense polarization of Thai society. It not only curtails criticism of the monarchy, but also serves to curtail criticism of other sensitive issues. More importantly, cyber-bullying amplifies and privatizes the effects of the draconian laws in the digital world.

This article is based on the writer’s research which is expected to be published this year.