At a prison in Samut Prakan Province, Mohammad (an alias), a Palestinian refugee from Syria, told us, “Please tell my wife for me, that I hope to return to her and our baby soon.” Having fled wars several times in his life and repeatedly becoming a refugee in foreign lands, the only reason he was charged with making and using a counterfeit passport in Thailand was that he dared to take on a little hope.

Hope for Survival

Mohammad’s destiny to become an illegal-entry refugee in Thailand is not a strange story. Thailand has a long history of providing temporary shelter in camps along the border to refugees from Indochina in the past and refugees from Myanmar at the present; arresting those who seek refuge outside the camps is nothing new. But what is new for Thai people is that since the end of last year, approximately 20 fugitives from Syria, including little children, have been arrested in Thailand while en route to a safe haven. Like Mohammad, many Syrian refugees arrested in Thailand are well educated and from middle class families. They have more in common. First, they are arrested and imprisoned in Thailand on the same charges – making and/or using counterfeit passports. Second, before they were arrested at Suvarnabhumi Airport, they aimed to transit Thailand for other destinations like Sweden, which safeguard and fully respect their rights. Third, their travel plans were completely arranged and dictated by illegal smugglers, who also gave them the fraudulent passports. Finally and most importantly, all of them fled murder, torture, enforced disappearance, starvation, and gross violations of human rights in the Syrian Civil War.

Beginning on 15 March 2011, the uprising in Syria which at first appeared to be peaceful, turned violent and later escalated into a Civil War, which is still going on. According to the Oxford Research Group report “Stolen Futures”, by the end of August 2013, the conflict had killed 113,735 civilians and combatants, among them 11,420 children aged seventeen or less.

In September 2013, the United Nations published the Report on the Alleged Use of Chemical Weapons in the Ghouta area of Damascus on 21 August 2013, concluding that “chemical weapons have been used (on 21 August 2013) in the ongoing conflict between the parties in the Syria Arab Republic, also against civilians, including children, on a relatively large scale”. On 12 February 2014, at the Twenty-Fifth Session of the Human Rights Council, another UN report by the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic was published, suggesting that the Syrian government was responsible for the enforced disappearance of civilians, which constitutes a crime against humanity.

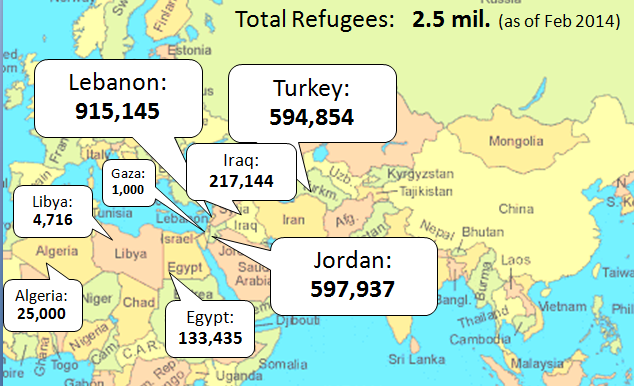

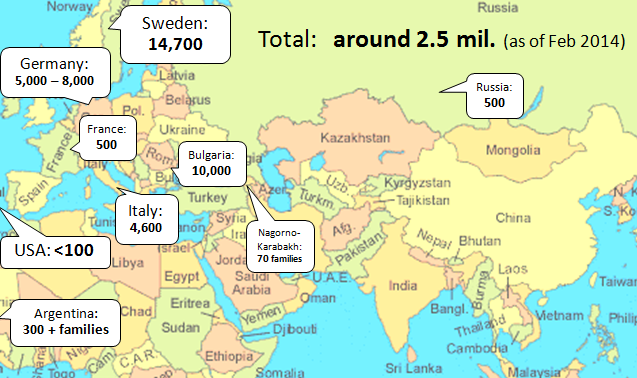

In the international arena, evidence of gross human rights violations and crimes against humanity in Syria is ample and clear; all that Syrian refugees need is simply greater international political will and real action. According to the United Nations in February 2014, nearly nine million people, or more than one third of the Syrian population, have been displaced since the conflict broke out, with 6.5 million internally displaced and 2.4 million refugees in neighbouring countries, mostly Lebanon, Jordan, and Turkey, but smaller numbers in a few European countries – Sweden, Germany, Bulgaria, Italy, and France. When EU member state Bulgaria experienced an unprecedented influx of Syrian refugees and sought EU solidarity to relocate some of them to other EU countries, it was unlikely that the rest of EU members would agree.1 Unsurprisingly, the EU’s actions towards Syrian refugees have been perceived by international NGOs as too little and too weak.2

However, the announcement in September 2013 by the Swedish Migration Board that they would grant permanent residence to refugees from Syria gave Syrian3 refugees a sense of hope. Since then, a number of Syrian refugees with their eyes on Sweden, including Mohammad, have transited Thailand.

Hope for Protection

Like Mohammad, refugees from Syria do not have many choices, particularly during this critical time. They have to choose between ‘stay’ or ‘flee’, ‘live’ or ‘die’.

“The government-supported forces closed the Yarmouk Camp, where we lived and stopped all humanitarian assistance to the camp residents. We had nothing left to eat; people starved and were dying,” Mohammad recalled the situation in his hometown in Damascus before he and his family escaped.

Unfortunately, Mohammad’s choice of flight, like many other refugees, caused him more trouble. This is because refugees are often in a vulnerable position. They are usually subject to deprivation of liberty, forced to take unsafe modes of travel, lack well informed choices, and are hence vulnerable to exploitation by traffickers and smugglers.

“My agent (smuggler), who was also a Palestinian from Damascus, said in order to get to Sweden, I had to travel through Thailand with a (fraudulent) EU passport, as Thailand has entered an agreement with the EU to allow refugees from Syria to transit en route to EU countries without criminalization,” Mohammad said.

“When I asked him for affirmation, as my daughter was still very young, he said that he had also taken the same route and now he was in UK, pending asylum. He also said that he was Palestinian; he would definitely not trick me,” he went on.

“Not until I was arrested did I realize that I was such a fool to believe his scam.” His voice started to break.

Because refugees commonly take irregular modes of travel in order to save their lives in critical times, international refugee law protects them from prosecution for irregular entry or using false documents.4

“However, as Thailand is not party to the Refugee Convention and its Protocol, we always find classic excuses for not respecting refugee rights. But we have to respect the human rights of refugees, as they are also human,” said Kohnwilai Teppunkoonngam, a human right lawyer.

“Thailand is party to several international human rights instruments, including the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), the Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (CAT) and the Convention on the Rights of the Child (CRC), which respect the right to life and protection from torture of all persons. Moreover, Thailand is a signatory to the Protocol against the Smuggling of Migrants by Land, Sea and Air, supplementing the United Nations Convention against Transnational Organized Crime (Protocol against Illegal Smuggling) and ratification is underway. Additionally, Section 82 of the Constitution of Thailand stipulates that Thailand shall comply with human rights conventions to which it is party,” Miss Kohnwilai went on.

“I do not agree that it is just to criminalize refugees who are trying to save their lives, who have been subject to torture, or who have fallen victims of illegal smuggling crimes, especially when we claim that we hold to the spirit of rule of law, human dignity, and the rights and liberties of all persons, regardless of their backgrounds.”

“Our criminal law and immigration law must change, until we have a good new law in place; just like we have the Anti-Human Trafficking Act B.E. 2551,” Miss Kohnwilai concluded.

Hope for Human Dignity

When asked why he would like to go to Sweden, Mohammad immediately replied, “Because Sweden respects the full rights and dignity of being human”.

But when asked where he would return to when his case was over, Mohammad paused a while and replied, “I don’t know; I have no home.”

Like many other Palestinians outside the Palestinian Territories, Mohammad’s family have fled wars several times in their lives. Before he was born, his family fled the Israel-Palestine Conflict to Shatila Camp in Beirut, Lebanon, in 1948. Later, in 1982, when Mohammad was just about 10 years old, troops allied to Israeli invaded the Shatila Camp and exterminated Palestinians, including children. Luckily, Mohammad and all his family managed to escape from the camp and sought asylum in Yarmouk Camp in Damascus, Syria.

“But I can’t return to Syria; it’s still unsafe. Besides, I lost my house, my car, my property, everything there,” Mohammad said.

Mohammad spoke about his personal life and his continuing hopes “The few treasures I still have and cherish are my life, my love for my beautiful wife and little daughter and my knowledge. My wife is Jordanian, but my little daughter is stateless like me, as the law in many Arab countries only recognizes nationality through the father.”

“Hopes are both bliss and pain, even very simple ones, like mine. It is always painful to realize that I may lose any one of them one day, but it is blissful to just continue to hope,” He went on.

Mohammad’s hopes are not unusual. They are actually in every human being. But for refugees like him, even just the hope for basic rights can be exploited by traffickers and smugglers.

Miss Kohnwilai likened Mohammad’s case with trafficking cases. “It’s impossible to be victim and criminal at the same time. Imagine the case of a trafficked woman who is tricked into becoming a sex worker. Will she be charged as an accomplice in the sexual trafficking business?”

When the law criminalizes the victims, they lose hope.

“My clients who have faced continuous abuse and injustice always ask me whether their cases would win. I always reply to them that if they lose hope, we will lose,” Miss Kohnwilai said.

* Ms. Kohnwilai Teppunkoonngam is a human rights lawyer and LLM student in the National Institute of Development Administration (NIDA). She previously worked in the fields of human rights, child rights, statelessness, asylum, anti-trafficking and migration for United Nations and international NGOs for more than 5 years. In the past, Ms. Kohnwilai also contributed to numerous reports and researches for Lawyers’ Council of Thailand’s human rights subcommittee on ethnic minorities, stateless, migrant workers and displaced persons.

[1] Euractiv. (9 October 2013). “EU Ministers Discuss Burden-Sharing for Syrian Refugees, African Migrants”. From http://www.euractiv.com/justice/syrian-refugees-african-migrants-news-530952

[2] Human Rights Watch. (17 March 2014). “EU: Act Now to Help Syria’s Refugees”. From http://www.hrw.org/news/2014/03/17/eu-act-now-help-syria-s-refugees.

[3] Swedish Migration. (5 September 2013). “New Judicial Position on Syria Opens up for a Higher Number of Permanent Residence Permits”. From http://www.migrationsverket.se/English/About-the-Migration-Board/News-archive/News-archive-2013/2013-09-05-New-judicial-position-on-Syria-opens-up-for-a-higher-number-of-permanent-residence-permits.html.

[4] See Article 31 of Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees