More than ten years after the war on drugs wreaked havoc on many Lahu ethnic minority families in the hilly northern Thai-Myanmar border, arbitrary abuses and discrimination from Thai state authorities continue as they struggle to come to terms with their traumatic past.

It was almost noon and the sun shone mercilessly bright above a small single-room shack, roofed with bamboo thatch. Emerging from its creaking door, Na-ue Jalo, a 68-year-old Lahu widower, smiled faintly and gestured for us to enter her modest home. Living in a run-down bamboo house with a nephew with physical challenges and a cat, she told us that she should fix the house before the approaching monsoon rains. At her age, however, fixing an old wooden house inherited from her husband, Jawa, could be too much of a task for her. Not seeing even a glimpse of her husband’s shadow for more than decade, Na-ue said “I still have hope that he might one day return” while casting her eyes downwards, staring at a beam of light through a crack in the bamboo floor.

Like Na-ue, many other families of Lahu, an ethnic minority in northern Thailand, are still tormented by the unknown fate of their loved ones who disappeared during the height of the ‘war on drugs’ initiated under Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra’s administration in 2003. According to Human Rights Watch, between February and April 2003, the controversial PM’s measure to crack down on the narcotics trade cost almost 3,000 lives, nearly half of which were not related to drug trafficking. As they struggle to overcome their losses, arbitrary arrests, evictions, and other forms of unfair treatment by the Thai state authorities continue as if salt is being rubbed into their open wounds.

Na-ue Jalo, a 68 years-old Lahu widower, whose husband, Jawa, disappeared after he was arrested by the border rangers in the midst of the war on drugs

Wounds that don’t heal

Living along the Thai-Myanmar border districts of Mae Ai, Fang, Chai Prakan, and Chiang Dao of Chiang Mai and Mae Sai District of Chiang Rai, one of the most active drug trafficking routes from Wa State in Myanmar, many Lahu families bore the brunt of the war on drugs.

Although about 90 per cent of about 120,000-150,000 Lahu ethnic have Thai citizenship and more than half can speak Thai, they are still viewed by the Thai authorities as foreigners. Coupled with unfair stereotypes that the Lahu and many hill minorities are opium farmers, forest encroachers, and narcotics traffickers, they suffered torture, summary executions, and enforced disappearances during the anti-drugs war. Sila Jahae, the President of the Lahu Association who has been active in fighting for justice for the Lahu and other hill minorities, was one of those who suffered such a fate.

Sila Jahae, the President of the Lahu Association who has been active in fighting for justice for the Lahu and other hill minorities. He himself suffered from torture and arbitrary detention in the hands of state authorities in 2003

Sila was detained in a Ranger camp in Fang District in Chiang Mai twice in 2003. He reported that the Rangers put him and other Lahu tribesmen in holes 2-3 metres wide and four metres deep. At the detention facility, they were repeatedly brought up from the holes for interrogation and beaten, threatened with execution, or electrocuted. Sila’s father is also one of the victims of the war on drugs. Although he himself could not recount the ordeal because of his neurological complications, Sila told us that his father was taken away from a lychee farm and put into the hole under false drug charges for two months.

“We urinated and excreted in the detention hole.” Sila recounted his trauma. “Sometimes the officers would kick and use their rifles to hit 8-10 detainees who were loaded into each tiny hole. There were three holes all together.”

According to Tyrell Haberkorn, an expert on violence and human rights violations in Thailand from the Australian National University, policies that usually lead to such violations are ones that create grey areas for the state officials.

“In case of the War on Drugs, the policy was just vague enough for the state officials and gave a wide range of space. They were told to ‘deal with the drugs problem’ but Thaksin or people under Thaksin never said how they should deal with it. That was taken as a signal as to do whatever you need to do,” said Haberkorn.

Sila said that the Rangers once told him “Thaksin (the former PM) has allowed us to arrest you people dead or alive.” He added that he does not know if Thaksin really gave the officers a blank cheque to arbitrarily persecute and kill Lahu people through drug allegations.

The holes used to detain Lahu people and other who were accused of drug trafficking during the narcotic war, which were already buried

In addition to arbitrary arrest and detention, the Lahu Association President mentioned that when the authorities came to arrest Lahu people, they tended to search houses and confiscate Lahu households’ valuables without returning them. Since many Lahu families, especially those who cannot read or write Thai, usually keep cash, gold, and other possessions in their homes, some lost their life savings and even vehicles.

Jadae Kae-ka, 47, another Lahu who was put into a hole for five days during the war on drugs in 2003 and remained in custody on drug accusations for another three months, told us that the Rangers searched his house and took 60,000 baht in cash. “The officers would mark well-to-do houses and come to search them,” said Sila. “Some Lahu people also made false drug accusations against each other. In 2006, 30-40 people fled to Myanmar.”

Jadae Kae-ka, 47, another Lahu victim of the war on drug

For other Lahu, the cuts of the war on drugs go much deeper. According to Sila, more than 20 Lahu have suffered enforced disappearance at the hands of the Army Border Rangers and the Thai police during the purge on drug trafficking networks between 2003 and 2006.

The Ja-ue family of Nong Pai village in Fang is one such family. In February 2005, during the New Year celebration of the Lahu, the family lost five members forever. Naga, the eldest and the mother of four of the family, told us that Jaka, her son, and Yalo and Nasi, a son and daughter-in-law, disappeared without their bodies ever being found, while Pichit, her husband, and Jakaa, the eldest son, were summarily executed. The bodies of her husband and eldest son were found the next day after the five were arrested on drug allegations. The family added that they were shot in the head with bruises and other injuries all over their bodies. The media at that time reported that Pichit and Jakaa were summarily killed by the authorities for trafficking drugs, but the family maintained that they were not involved in the narcotics trade.

As for the other three, however, no one knows what happened to them after they were arrested. “I still believe that my children are alive,” said Naga. Napla, the sister of Jaka and Jakaa, told us “Deep down, we still have hope that they might still be alive.” She added “These days, when the authorities come into the area, we’d be afraid”. Nothing concrete has been done to investigate the deaths and enforced disappearances of the Ja-ue family.

Naga Ja-ue (left) holds a picture of Pichit, her late husband, while her daughter, Namai Ja-ue (right), holds a picture of Jakaa, her brother, both of whom were summarily executed by the authorities in 2005

According to Jahae Kirirasmi, the Ador, or Lahu religious leader of Nong Pai Village, the unknown fates of many Lahu who disappeared during the war on drugs continue cast a dark shadow upon many Lahu families because the families could not perform proper religious ceremonies for their lost members. He added that his son-in-law was also killed during the height of the narcotics war.

Unending Ordeal

Although it has been more than the decade since the war on drugs was implemented and scrapped altogether when Thaksin was ousted by the coup d’état in 2006, there has been no prosecution of Rangers or police officers who were allegedly involved in torture, summary killings and enforced disappearances in Lahu communities.

Arbitrary arrests and prosecutions of Lahu people by state authorities continue until now. On 25 November 2014, military officers arrested Jako Ja-mea and charged him with possessing narcotic substances after they reportedly found illicit drugs around his farm and house. In the case file, the officers wrote that a spy reported that Jako possessed illegal drugs and was involved in a drug trafficking ring with two other Lahu in Tha Ton Subdistrict of Mae Ai. According to the Peace Foundation, a civil society group which has been providing legal assistance to many Lahu and other ethnic minorities in Chiang Mai and Chiang Rai, however, there are many inconsistencies in the report of Jako’s arrest.

The Foundation pointed out that the authorities did not record the name of the ‘spy’ who made the accusations against Jako. Moreover, the officers mentioned in the file that three Lahu tribesmen are involved, but one of the suspects was released on the day of the arrest. The Foundation added that contrary to the case file, which states that 2000 narcotic pills were found in a hole next to a corn field of the suspect and another 60 pills next to Jako’s house adjacent to a village creek, the footage evidence shows that there is no corn field in the area and that the house of the suspect is nowhere near the creek.

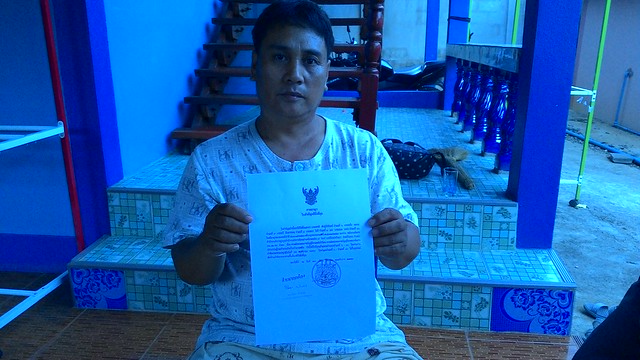

Nadao Aimu, Jako’s wife, maintains that her husband is innocent. She said that the authorities and another Lahu tribesman who owes her husband money planted drugs on Jako. Speaking in Lahu, Nadao added that the officers also hit Jako’s head with batons to the point that he lost consciousness and claimed that they had to do so to prevent his escape. Jako is still in custody.

Nadao Aimu, Jako’s wife, who maintains that her Lahu husband is innocent

In 24 March 2013, police officers stopped the pickup truck of Thongchat Panpakarin, a Lahu man, when he was driving home in Fang District of Chiang Mai from a festival with four other Lahu, five Hmong, and two Lisu. The officer searched the car and claimed that the car was stolen from another person before arresting Thongchat and the others. The police took them to the Narcotics Control Board district centre where they were interrogated and later informed that they were charged with drug trafficking.

“The narcotics control officers detained us there for two days. They asked me if I know the guys from other tribes whom I offered a free ride to and when I said I didn’t know them before, they repeatedly hit and electrocuted us,” said Thongchat. “They put plastic bags over our heads and punched us; when we were about to faint from suffocation, they removed the bags and questioned us all over again.” He added that the interrogation officers tried to force him to sign a statement, but he refused because the officers did not allow him to read it.

After two days of interrogation, the police brought Thongchat and 11 other suspects to Bangkok and imprisoned them in Bangkok Remand Prison during the trial. In the end, two Lisu tribesmen who fought the case up the Supreme Court received the death penalty and five Hmong pleaded guilty and were sentenced to long years in prison. Thongchat and four fellow Lahu, who always pleaded innocent, were acquitted after being held in the remand prison for a year and nine months.

“There was no apology. My family had to spend a lot of money to go visit me in Bangkok and my daughter’s pickup truck was confiscated for 11 months, but there is no compensation whatsoever from the authorities,” said Thongchat. “I am fortunate because my family is supportive but for the other Lahu their wives left them.”

Thongchat Panpakarin, a Lahu man who was imprisoned in Bangkok Remand Prison for almost two years, but was later acquitted from the drug trafficking charges

Sila said that it is easy for the authorities to randomly pick on and abuse Lahu people along the border because of the lack of development in the region and the fact that most Lahu families are undereducated. “In the past they thought of us as vegetable or fish; if they wanted to kill then they just killed us,” the head of the Lahu Association told us.

In another recent case, four Rangers stopped Anuwat Pudlek, a Lahu teenager driving a motorcycle at a check point between Nong Pai and Huai Nok Kok villages in Fang District, Chiang Mai, in late 2014. He was taken into the bushes where he was held by two officers while another beat him and asked if he had been taking illicit drugs. When he denied this, the Ranger continued to hit him until he had no choice but to confess to stop the beating.

Anuwat told us that the Rangers simply let him go after he confessed as if nothing had happened. He added that the officers might have beaten him because they mistakenly thought that he was another Lahu who messed with them earlier.

Anuwat Pudlek, a Lahu teenager, who was randomly stopped and tortured by Rangers

Under the current junta regime, adding to the arbitrary abuses and discrimination, the forest protection policy of the military government has made numerous Lahu families jobless. After the junta’s National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO) issued Order No. 64/2014 in June 2014 to crack down on encroachers in protected areas and poachers, hundreds of acres of farmland used by the Lahu people have been reclaimed by the Royal Forest Department. Although according to NCPO Order No. 67/2014, the forest policy does not apply to poor people and those who had settled in protected areas prior to the enactment of Order No. 64/2014, the authorities took a hard stance against Lahu communities who have been settled in the area for many generations. In July 2015, Pa-ae Kirirasami, 57, Witoon Kiriratsami, Pa-ae’s 22-year-old son, and Jakui Japalo, 37, farmers of Huai Nok Kok Village, Fang District, have been charged with encroaching into Doi Pha Hom Pok National Park and assaulting officers on duty.

Pa-ae, the religious leader of the village, told Prachatai in May 2015 that he was beaten by the authorities, his right ring finger was broken and he had to have six stitches on his scalp. He said that on that day he went to check the irrigation system of the village. When he ran into some National Park officials, he ran away. He said the officers caught him and beat him on the head. Later his son and other villagers came to rescue him and tried to take him to the hospital. The National Park officials instead allegedly blocked and surrounded the villagers. The situation became tense and both sides engaged in a brief clash. The incident ended when the military came to impose law and order at the request of the National Park officials. The village’s spiritual leader added that he has farmed there for the last 20 years.

Pa-ae Kirirasami, an Ador of Huai Nok Kok Village, who is now charged with land encroachment along with two other villagers

Kam Nalu, the former Ador of Huai Nok Kok, told us “We can’t farm and we are going to starve. We usually start farming in May, but now we can’t do anything.” Sila pointed out that the authorities reclaimed the farmlands of Lahu people, but allowed Thanatorn Orange Farm, a large orange producer in the area who occupies more than one square kilometre of land, to continue farming. “Why do they let the capitalists do it [farm] while picking on the villagers who only own tiny plots?” asked the Lahu Association leader.

The Response from the Authorities

The Police officers in charge of tackling drug trafficking networks admit officers did make some mistakes and abuses during the implementation of the War on Drugs policy, but they did not occur often.

According to Pol Col Somkiat Wannasiriwilai, Deputy Commander of the Narcotics Suppression Bureau (NSB) of the Royal Thai Police, the War on Drugs policy under the Thaksin regime was like “hard medicine.” As the Deputy of the Special Task Force of the NSB in Chiang Mai from 1997 to 2009, he said that the policy at that time was to suppress and crack down on the narcotic trade in “all dimensions” because of the rampant drug trafficking activities along the Thai-Myanmar border.

In reference to the allegations of summary executions made by human rights groups against officers, he said “It [the policy] was ‘hard medicine’ that might result in some mistakes, but in most cases, as far as the police were concerned, the authorities were not involved.”

Pol Col Somkiat told Prachatai that he, however, does not have information about alleged abuses against the ethnic minorities by military officers and Border Rangers between 2003 and 2006.

The NSB Deputy Commander added that many ethnic minorities along Thailand’s northern border are still engaged in narcotics abuse and drug trafficking simply because of their low income and the fact that they live right next to the border where drugs can easily be smuggled in from Myanmar.

“They can earn about 50,000 baht per package of narcotics, usually containing about 2000 pills, an amount which would take them a year or more to earn from farming,” said Pol Col Somkiat.

Another high-ranking police officer in the NSB who asked for his name and position not to be identified, said similarly that there were mistakes by the authorities during the height of the drugs war, but the figures that human rights organisations such as Human Rights Watch cited were too far from reality.

“I can say that about 90 per cent of those killed during the height of the drugs war were involved in narcotics abuse or drug trafficking,” said the anonymous officer. “This is not to say that there were no errors committed by police officers of course. Some officers were investigated and indicted for alleged abuse of power during that time, but I have not been following the outcome of these cases.”

The high-ranking officer added that many ethnic minorities summarily killed during the drug war were in fact killed by rival drug trafficking networks or their own people who did not want them to open their mouths about the network’s activities. “There were some cases where certain suspects were killed only a few days after they were released on bail,” said the anonymous officer.

When asked about allegations that some officers took the possessions of ethnic minority families after carrying out searches for narcotic substances in their houses, he said that there were probably some, but the alleged officers were usually investigated afterwards.

Like Pol Col Somkiat Wannasiriwilai, he said that he has no information about alleged abuses against ethnic minorities by the military and Border Rangers.

Prachatai tried to contact military personnel in charge of the Ranger units who were deployed in Chiang Mai Province during the drugs war, but received no reply.

A typical Lahu village along the Thai-Myanmar border in Fang District of Chiang Mai Province where most habitants are farmers

Back in the dimly lit wooden shack with no electricity of the old Lahu widower, Na-ue Jalo, we were offered some lychee to refresh ourselves during an unbearably humid noon. Speaking of her lost lover in the Lahu dialect with a cracking voice she told us that Jawa, her husband, was beaten by officers and other Lahu detainees who were forced to join the beating. Although she was told that he is dead and that the officers dumped his body in a hole somewhere, the 68-year-old Lahu woman is still waiting for a reunion with her husband, dead or alive. Walking us out of her compound, she stared at the thick clouds which were beginning to form above the village’s hills. With the help of Sila and other villagers perhaps she would be able to repair her shack in time before the monsoon arrives, but who knows how many monsoons it would take to wash away her sorrow.

Prachatai English is an independent, non-profit news outlet committed to covering underreported issues in Thailand, especially about democratization and human rights, despite pressure from the authorities. Your support will ensure that we stay a professional media source and be able to meet the challenges and deliver in-depth reporting.

• Simple steps to support Prachatai English

1. Bank transfer to account “โครงการหนังสือพิมพ์อินเทอร์เน็ต ประชาไท” or “Prachatai Online Newspaper” 091-0-21689-4, Krungthai Bank

2. Or, Transfer money via Paypal, to e-mail address: [email protected], please leave a comment on the transaction as “For Prachatai English”