January 2016 marked more than four years since Somyot Prueksakasemsuk, social activist and former editor of Voice of Taksin magazine, lost his freedom for the publishing of two articles in the magazine which were deemed to fall within the domain of lèse majesté. (see Somyot's case on our database

here)

Four years is a long time for those with hopes and plans, especially when those years are spent behind the walls of a prison. For some prisoners, four years is long enough to extinguish the lights in their eyes. But Somyot’s spirit of resistance cannot be destroyed by the cell that confines him. This spirit was in evidence in the blurry picture of him raising his hand and beaming out a smile that spread around news

websites in November 2015.

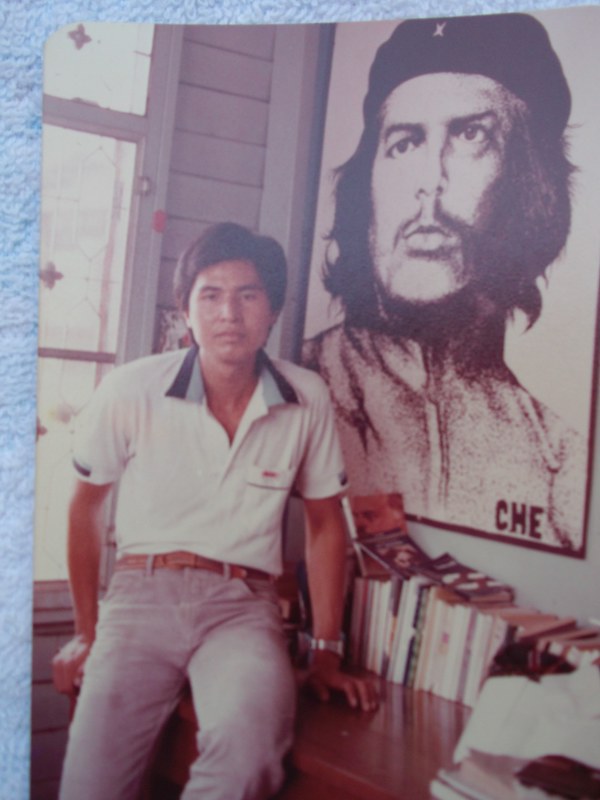

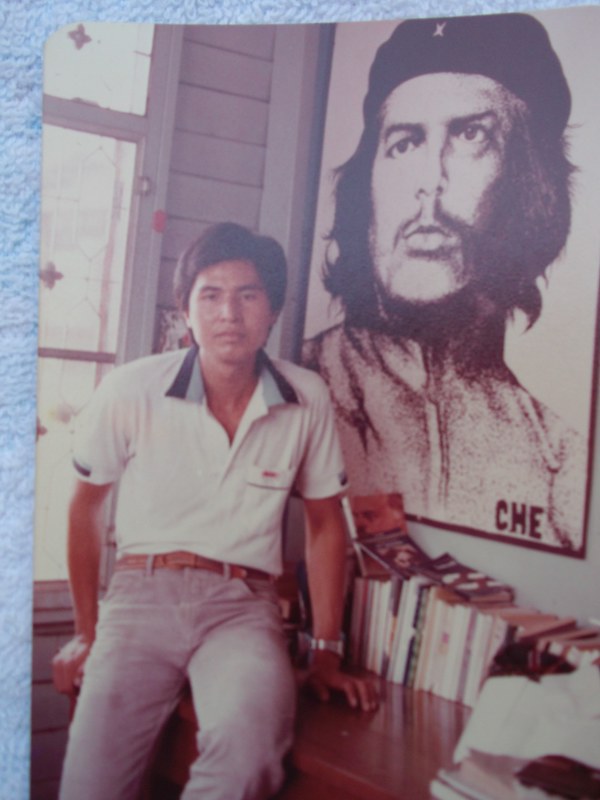

Somyot as a young man (photograph provided by Sukanya Prueksakasemsuk,)

The extinguishing of his freedom

In addition to his usual work as an editor and social activist, in 2006 Somyot began to supplement his income by leading tours.

On 30 April 2011, Somyot travelled with the participants in one of his tours to the Thai-Cambodian border. At the checkpoint at Aranyaprathet, Somyot queued for his documents to be checked and stamped along with everyone else. The immigration officials discovered that there was a warrant for Somyot’s arrest from the Criminal Court. They took him into custody and liaised with headquarters to send him back to Bangkok. Somyot was informed that the accusation against him was defamation of the king under Article 112, which is one of the gravest accusations one can face during this era. The accusation stemmed from publishing two articles deemed to defame the king in Voice of Taksin magazine, which he had edited since 2010.

Sukanya Prueksakasemsuk, Somyot’s wife, said that he is the kind of person whose view of the world is glass half-full. He is the kind of person who remains hopeful, even when he is in a terrible predicament.

Perhaps this is because Somyot has been absorbed in issues for which it is difficult to secure victory, such as workers’ rights and the amendment of Article 112, for his entire working life. With respect to his case, Somyot was confident that he would meet with fairness as he fought it, including being granted the right to bail. Over the past four years, Somyot has submitted 16 applications for bail and held out hope for justice. Unfortunately, every request resulted in disappointment. The court denied Somyot’s requests on the basis that the case against him is a grave one that carries a severe punishment, and so he might flee if released. Even though Somyot has been denied bail while he fights the case, he has chosen to fight it all the way to the end.

Life within the walls of the prison

Somyot at the Phetchabun provincial court

Adjusting to prison life is not an easy matter. In addition to the restrictions of their freedom, prisoners must live under strict rules and regulations that limit eating and other aspects of life. Upon first entering prison, Somyot often complained about the food, but he later adjusted and these complaints faded away.

In addition to the issue of food, Somyot and other prisoners must face the tedium and loneliness that come from the monotony of the routine inside the prison. Somyot uses books in order to ease his loneliness. But the books available in the prison library are limited and the majority are dharma [Buddhist religious] books and novels. Somyot relies on his friends and family to send books on society and history, such as books about the lives and struggles of Mahatma Gandhi and Nelson Mandela. Reading the biographies of freedom fighters who have been imprisoned boosts Somyot’s morale to a degree. But it is the visits from his many friends and other supporters that really make a difference and serve as encouragement for him to persist despite being locked up behind bars.

After the dispersal of protests in 2010, many people were arrested and then sentenced to terms inside the Bangkok Remand Prison. The prison allowed exceptions to be made to the rules for visitors. The political prisoners were allowed to go out in large groups to visit their friends and relatives. This meant that the families, friends, and supporters of the same political stripe could visit all those who were imprisoned at once.

Sometimes the visitors were so numerous that they spilled out of the rooms. During this period, the relatives who looked after Somyot came to see him, as did those who shared the same ideals, including those whom he had never met before as well as his friends. People came to ask him for advice on the path that political activism should take. The conversations and encouragement from the visitors fell like nourishing raindrops that kept Somyot’s morale from drying up.

The changes wrought inside the prison by the coup

On 22 May 2014, a group of soldiers fomented a coup in the name of the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO). They promulgated many laws and regulations that impacted the rights and freedom of expression of the people in the country, including prisoners. During the first two months after the coup, the Bangkok Remand Prison still allowed political prisoners to be visited by those who shared their ideals. But plainclothes officials photographed the visitors and stood and observed in the visitors’ waiting area. Then, in July 2014, the NCPO issued Order No. 84/2557, which appointed a new director-general of the Department of Corrections.

The new director-general brought a stricter visitor policy along with him. The rule which stipulated that each prisoner had to make a list of no more than ten people who could come visit him was adopted long ago but only implemented strictly after the coup. In addition, those imprisoned for violation of Article 112 had to meet visitors in a special room with a thick glass divider that necessitated the use of telephones to communicate, rather than the old method of communication in which yelling could suffice. Further, restrictions were placed on accessing the news. Prior to the coup, prisoners were sometimes able to read old editions of newspapers. But after the coup, even old news was forbidden.

Prior to the coup, Somyot was already deprived of freedom. But the coup brought new, dire consequences to his life. After the “ten person rule” was enforced strictly, only relatives and a few close friends can come to visit him. Their conversations tend to be about life and his living conditions rather than the political situation. This makes a person with a political consciousness, like Somyot, feel suffocated. Prisoners also suspect that prison officials have bugged the room where they converse with visitors, which makes them unable to communicate freely.

In addition, the officials are much stricter about the books that can enter the prison. Many of the books sent by Somyot’s family since the coup have been returned. The books that were sent to him prior to the coup that he placed in the library were all sent back to his family as well. But none of this is as grave as another new aspect of Somyot’s life in prison after the coup, which is being trailed by prison officials. They follow Somyot and note whom he speaks with and what they talk about, and then report it to the prison commander. This is likely the most difficult thing for Somyot to withstand.

The substance of his ideals

The picture of Somyot smiling and raising his hand that circulated at the end of 2015 demonstrates that his morale has not waned, even as amidst a disheartening situation in which he has been without freedom for more than four years and in which life inside the prison has grown more oppressive since the coup.

One thing that helps keep Somyot’s spirits up within such a discouraging situation is the sense that he can still do things for others. An example is that a friend of Somyot’s visited him and Somyot asked the friend to buy him a toothbrush and tube of toothpaste. The friend visited him again only a few days later and Somyot asked the friend to purchase another toothbrush and another tube of toothpaste. Somyot had already given the first set to a new prisoner. Somyot’s friend said that he often kept bars of soap and toothbrushes in reserve for new prisoners whose families lived far away and could not come to buy necessary items for them. In addition, Somyot often chats with new prisoners and gives them advice about how to adjust to life in prison.

Somyot is well-known for his kindness in Zone One, the entry zone, of Bangkok Remand Prison. The political prisoners and other prisoners talked about a former prisoner who called after his release to ask after Somyot. While this person was in prison, Somyot helped him and gave him advice, and so he missed him after his release. Before the enforcement of the “ten visitor rule,” former prisoners also stopped by to visit Somyot. The people who visited and called were not only limited to former prisoners, but also included a warden from the Phetchabun prison, where Somyot had stayed for a short period while hearings were carried out in the province. While Somyot was held there, he organized his friends and family to collect donations of sweaters for the prison clinic to give to prisoners who did not have their own.

The figure behind the curtain of struggle

For the entire period of his imprisonment, Sukanya, Somyot’s wife, has been the one who visits him and sends him rice, fish, food and other necessary items, including steadfast encouragement. Sukanya explains that her employer allows her flexibility with time and so she is able to visit her husband once a week. Somyot does not have to worry too much about things at home, because Sukanya takes care of them. Her job is secure and their son has already graduated and is working. The only person left to worry about is their daughter, who is still studying. Somyot does not write letters to his wife, because he sees her nearly every week, but sometimes he sends letters to his daughter out of care.

The impact of Somyot’s imprisonment on his family is heavy, but perhaps not greater than they can bear. Somyot has always worked for nongovernmental or other civil society organizations, and so his income has never been his family’s primary income. His wife said that she has been the prime force in providing financially for the family from the beginning. The flexibility of her employer with regards to time means that she can allocate time to visit Somyot. Aside from this, both children are grown up and understand what has happened.

The Prueksakasemsuk family is an open-minded one. Sukanya knows well that Somyot’s work cannot be the main source of the family’s income. But she respects the work he does and so chose to spend her life with him. She also respects that he chose to fight his case all the way rather than ending the case by confessing so that he could ask for a royal pardon. Somyot’s wife and children respect his decision and offer support in the form of encouragement. His family’s support is another one of the reasons for Somyot’s continued perseverance after nearly five years of being deprived of freedom.

Five years down, six more to go

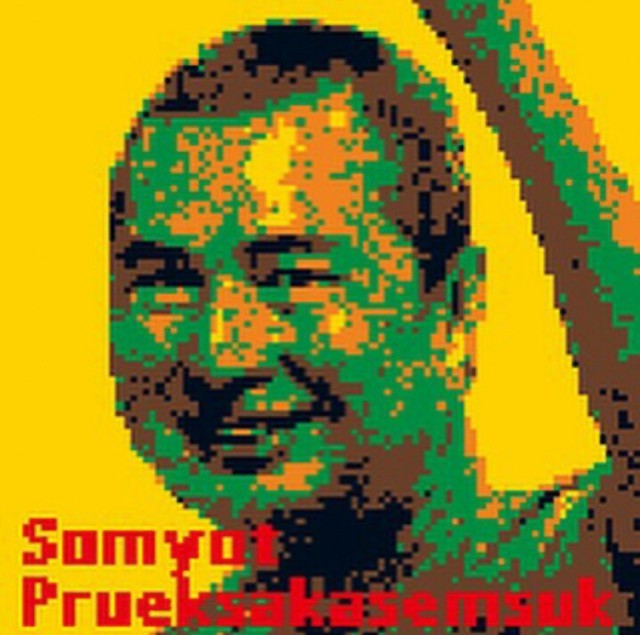

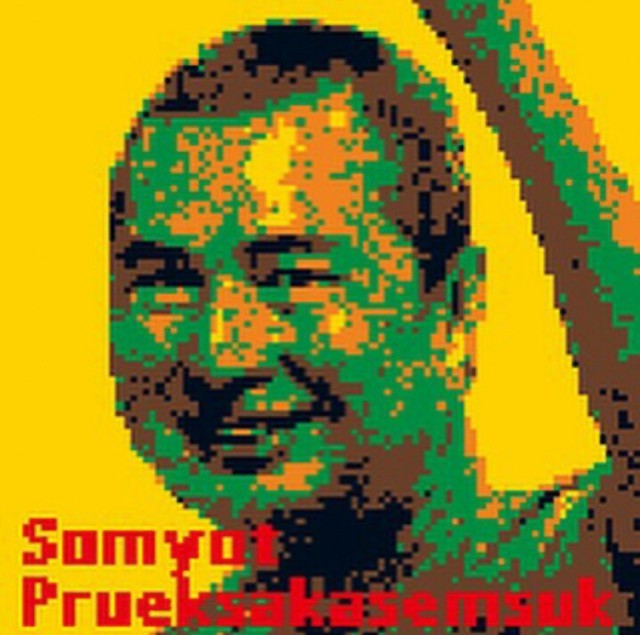

A picture of Somyot by Ai Wei Wei

On 23 January 2013, the Criminal Court sentenced Somyot to ten years imprisonment under Article 112, and added an additional year of imprisonment that had previously been suspended, from a case of defamation of General Saprang Kalayanamitr. Somyot’s total imprisonment is therefore eleven years. In September 2014, the Appeal Court upheld the sentence of the Criminal Court. If the soon-to-be-released Supreme Court decision is in line with that of the two lower courts, then Somyot will have around six years and four months of his sentence remaining.

Given the present political situation, the possibility that the Supreme Court will depart from the earlier decision is faint, but Somyot still holds out hope. In October 2015, the Supreme Court reduced the Article 112 sentence of Ekachai from three years and four months to two years and eight months. Somyot’s hope is that the Supreme Court will grant a partial reduction to his sentence. But if the Supreme Court does not reduce his sentence, he is prepared to serve the full term. Somyot will not request a royal pardon.

Even though requesting a royal pardon would likely mean that Somyot would be released and would return to his family more quickly, Somyot is firm in his decision not to take this path. This is because Somyot is sincere in his belief that he has not done anything wrong. If he were to request a royal pardon, he would have to write an appeal in which he explained that he realized his crime and deeply regretted his actions. Even though this path would result in a swifter return of his freedom, it goes against his beliefs and would leave him imprisoned in another sense for the remainder of his life. So Somyot will fight his case all the way to the Supreme Court. If the Supreme Court judges him to be guilty, Somyot is prepared to accept the full term of the punishment. His family is ready to walk beside him as he faces hardship and awaits the day that they will bring him home from the prison