Since Thailand declared war on drugs 15 years ago, harsh suppression measures have been imposed and at the same time proven themselves ineffective. The number of drug offences continues to rise. Given the limited resources of the Thai justice system, Thai prisons are overcrowded, and over 70 per cent of inmates are convicted for drugs. In March 2018, the Department of Corrections revealed that Thailand had 334,279 inmates, 247,344 of whom were convicted for drug offences and most are merely users or retailers while the drug lords are rarely punished.

Policymakers in recent years have therefore proposed the slogan “a user is a patient,” the idea that drug users should be taken care of by hospitals or other healthcare agencies, rather than prisons. One genuine attempt by the National Council for Peace and Order (NCPO) is NCPO Announcement 108/2014 on the Treatment for Drug Suspects. The order allows suspects who caught in possession a small quantity of drugs to undergo rehabilitation in exchange for having their charges withdrawn.

Also, the NCPO is drafting a new Narcotics Act which, according to one drafter, will treat drug users more humanely. Jitnara Nawarat a member of the National Legislative Assembly responsible for revising the Narcotics Act, stated that the current rehabilitation is wasteful because it treats users as criminals as soon as the process begins.

Jitnara explained when users are arrested, they will immediately be sent to prison and detained there for up to 45 days. During detention, the authorities classify users based on their level of addiction and send them to receive treatment at appropriate agencies, which could be hospitals, military camps or private rehabilitation centres. Drug users have to undergo the whole process, which could take over a year; otherwise they receive criminal punishment. But even if they finish the session, their criminal records remain.

“Users are not really patients because they have to be detained in prison for at least 15 to 45 days. For them, entering the prison is equivalent to being arrested. The places of detention are also seriously overcrowded. It is like this because, by the time the law came into force, no extra budget was provided for the new measures. So prisons have had to be used instead of hospitals during the process of classification before rehabilitation. As a result, those who were prosecuted are ready to escape at any time. This is the waste of rehabilitation,” Jitnara stated.

Although the drafter confirms that the new law will improve the treatment of drug suspects, the readiness of Thai agencies to embrace the new measure remains questionable.

Net cast wide to find “patients”

One of the police methods to search for drug users is to set up security checkpoints and ask people passing by to take urine tests. If the test is positive, the user will be sent to a rehabilitation course regardless of their level of addiction.

Legally, police officers have no authority to perform a urine test unless they hold a certificate granted by the Office of Narcotics Control Board (ONCB). The urine test can be done only after a person is accused of a drug offence or driving under the influence. In practice, however, even taxi passengers have to undergo urine tests if the authorities ask.

Veeraphan Ngammee, of the Ozone Foundation, an NGO which promotes harm reduction in drug use, pointed out that the urine test is the easiest way for the authorities to find drug users as they have to meet annual quotas set by their commanders.

“The state believes that those who possess narcotic substances must be rehabilitated which leads to quotas in terms of numbers. They predict how many drug users each year should be the target for arrest to be sent to rehabilitation,” Veeraphan said.

However, Niyom Termsrisuk, Senior Narcotics Control Advisor at the ONCB, argued that although the police set a quota of around 62,000 drug cases per year, they only target drug dealers.

But the problem comes with the legal definition of “drug dealers”. Thai law distinguishes users from dealers based on the amount e they possess. To illustrate, those who carry more than five methamphetamine tablets are considered dealers although they have no intention to sell.

When the strict legal definition combines with the annual drug offence quota , many users every year are unnecessarily subject to rehabilitation without consent which leads to further ineffectiveness and a waste of resources.

Problems stemming from lack of consent

Dr. Lumsum Lukanapichonchut, Deputy Director of the Thanyarak Institute, explained that when patients do not consent to undergo rehabilitation in the first place, they are less likely to give true information to avoid unnecessary treatment.

“The urine test only tells whether at that time a person has narcotic substance in their body or not. To tell whether they are just a user or an addict, we have to talk in detail and the addict must tell the truth which is an issue where they have an interest one way or the other. They don’t tell the truth. They say things that make them look OK,” Lamsam said.

More importantly, not all users will be taken care by healthcare officials. Thai rehabilitation has three systems for different types of users. The first is the voluntary system for those themselves who choose to walk into a hospital to receive treatment. The second is the compulsory system for those who are arrested for minor drug offences and decide to undergo rehabilitation instead of criminal punishment. The last is the punishment system for those convicted for any crime who have a history of drug use.

According to the Public Health Ministry, in 2017, the voluntary system provided treatment for 67,413 cases, the compulsory system 24,834, and punishment system 20,700. Only those who voluntarily go to a hospital are certain to be treated by professional physicians while either security or administrative agencies take care of the other two systems. Patients under the compulsory system can be divided into two groups -- rehab with and without detention.

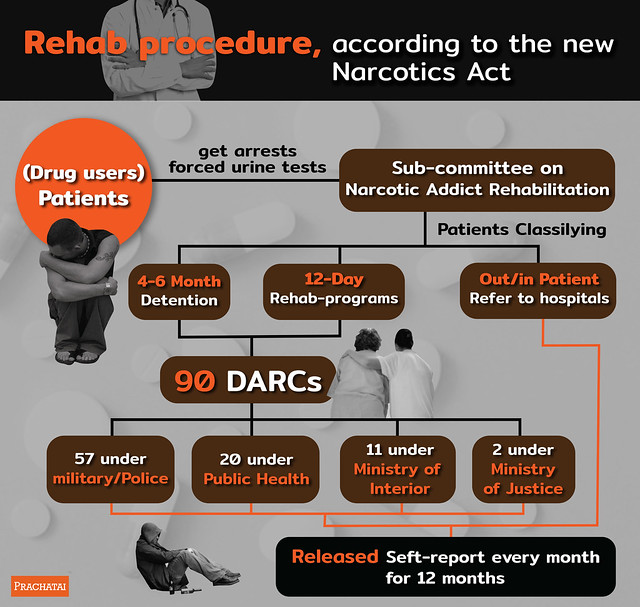

Patients in the first group will be detained for four to six months at a Drug Addict Rehabilitation Center (DARC). The second group also have to undergo a 12-day-long rehabilitation programme at this centre. After finishing the DARC session, both groups also have to report and pass a urine test every month for one year. If they fail to report for the urine test just once, they will receive criminal punishment. This reflects that the system end-goal is to force these people to stop using drugs, instead of helping them to use drugs safely.

Thailand has 90 DARCs across the country, 57 of them under the supervision of the military and the police, 20 under the Public Health Ministry, 11 under the Ministry of Interior and the other two under the Justice Ministry. This means that health experts are not involved in the care of nearly 80 per cent of the patients.

Shortage of resources and social stigma

Lastly, the punishment system is for inmates convicted of any crime who have a history of drug use. They will undergo rehab in the prison which detains them. With the current shortage of resources in overcrowded prisons the Department of Corrections cannot provide proper treatment to all inmates.

Pornpan Sinlapawuttanaporn, a psychologist from the Corrections Department (CD), revealed that Thai prisons have over 100,000 inmates with a record of drug use, but the Department has the capacity to take care of only some 20,000 cases per year. Most of the rehab programme uses Buddhist meditation and therapeutic communities conducted by wardens who receive training by CD psychologists.

Pornpan stated that CD only has 22 professional psychiatrists to take care of over 300,000 inmates in 142 prisons nationwide. The CD, therefore, has to hold annual training sessions to educate wardens about drug addiction therapy, but the problem remains as prison staff are reshuffled every year. For instance, a warden who currently works in drug rehab section might next year be shifted to the education section.

Untreated side-effects of drug use can also lead to more severe mental disorders, Pornpan added. She said the CD has provided treatment to about 3,000 inmates with mental illness and 300 of them were diagnosed as the result of drug use.

These stories show that Thailand still lacks the readiness to treat ‘users as patients’ which is what it tries to promote. According to Dr. Lamsam, the problem stems from the fact that the social stigma that sees drug users as threats and criminals remains very strong. This stigma is reflected in the healthcare system; for example, the social security fund does not cover drug addiction treatment.

Non-government employees who want to withdraw from addiction have to rely on 30-baht universal healthcare scheme, where the NCPO is trying to limit the budget. Although government employees’ welfare includes drug addiction treatment, fewer people use it since a record of drug treatment might sabotage their future careers.

“People in general still see drug users as criminals. In western countries, they don’t see drug use as a serious matter. It can be solved. They view drug users the same as people addicted to alcohol and tobacco. They see it as a personal problem, not a criminal problem. In Thai society, it’s not like that. So if we gradually fix this attitude, when people finish rehab, they can have a job and continue a normal life,” Lamsam added.

Prachatai English is an independent, non-profit news outlet committed to covering underreported issues in Thailand, especially about democratization and human rights, despite pressure from the authorities. Your support will ensure that we stay a professional media source and be able to meet the challenges and deliver in-depth reporting.

• Simple steps to support Prachatai English

1. Bank transfer to account “โครงการหนังสือพิมพ์อินเทอร์เน็ต ประชาไท” or “Prachatai Online Newspaper” 091-0-21689-4, Krungthai Bank

2. Or, Transfer money via Paypal, to e-mail address: [email protected], please leave a comment on the transaction as “For Prachatai English”