According to UNESCO’s definition, the humanities comprise religion and theology, philosophy and ethics, languages and literature. Questions about the state of humanities subjects in Thailand are asked today when the world situation indicates that the humanities are gradually disappearing from universities.

The Humanities Indicators were established by the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and their data shows that the proportion of those completing humanities programmes in 2015 compared with other subjects was lower than the previous the lowest point in 1985. Humanities graduates have the second highest unemployment rate after arts graduates. PhDs in the humanities in the US receive the lowest income compared to medicine, the physical sciences, the social sciences, engineering and education.

Illustration by Nattapon Kaikeaw

In March 2018, the Washington Post reported that the University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point was proposing the abolition of 13 majors in the humanities and social sciences and adding programmes with ‘clear career pathways’ as a way to address declining enrolment and a multimillion-dollar deficit. If a campus governance committee and the university Board of Regents approves, the process to close these majors will take place in 2020. Meanwhile, in the UK, information from the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA) shows that from 2012 to 2017, the numbers choosing to study languages, history and philosophy declined every year.

In Thailand, information from the Office of the Higher Education Commission (OHEC) shows that the number of humanities students in 2017 declined, but this reduction was related to an overall reduction of students in the country.

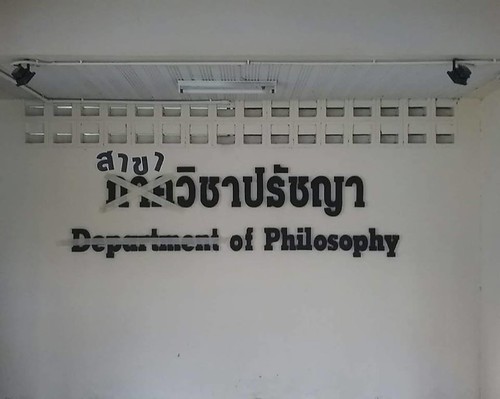

In March 2018, there was news that the Philosophy Department at Silpakorn University had been downgraded to a programme. This became a major story when teachers in the Department rose up in opposition through the media.

‘If it is a programme, then it will be administered centrally by the faculty. As a department like before, higher administrators cannot come in and manage certain things in the department. So it would still be a decentralized form of administration and ensure academic freedom,’ according to Komkrit Uitekkeng, an instructor in the department.

Facebook/ Komkrit Tul Uitekkeng

Facebook/ Komkrit Tul Uitekkeng

Viewed overall, many universities have been transformed into public autonomous universities, commonly known as ‘universities outside the system’, in the belief that this will liberate management and reduce regulation while still receiving some budget support from the state. At present, there are 23 public autonomous universities. Leaving the system leads to many structural changes including the downsizing of departments and internal agencies in faculties in the belief that this will increase efficiency.

At Srinakharinwirot University (SWU), all departments in the Faculty of Humanities have been abolished; these are psychology, library and information science, philosophy and religion, western languages, Thai and oriental languages, and linguistics. The existing curricula have been moved under an agency called the Centre of Undergraduate Studies, Graduate Studies and International Studies. Charn Rattanapisit, the head of the Centre, said that the change in the administrative structure responded to the question of autonomy and quality assurance of OHEC by focussing on the curriculum, and reduced administrative duplication by saving on the costs of department heads. There was no need for so many department heads at a time when financial support from the state sector was decreasing. But the disappearance of departments meant that the venue for communication among individuals disappeared and was replaced by one-way communication through e-mail.

‘The concept that universities must provide for themselves leads to adjustments in the old curriculum so that it can be sold to attract a new group of people to study. When there is a new curriculum, it will naturally affect the existing curriculum. The old curricula for philosophy, religion, linguistics and Thai language were completely unsellable. But it is not that humanities subjects will disappear. They will just be transformed into applied humanities,’ said Puttawit Boonnak, president of the philosophy and religion curriculum at SWU.

At the Faculty of Liberal Arts, Thammasat University, 14 departments have been merged into 5. Asst Prof Adisorn Muakpimai of the Faculty of Liberal Arts, TU, said that the merger of departments was the result of autonomy because of the administration’s belief that restructuring would create more flexible decision-making. But after the merger it was found that decision-making on some issues was not more flexible, such as recruiting new teachers, which was earlier divided by department. At present, it was done collectively, but academic freedom was not reduced.

At the Faculty of Humanities, Chiang Mai University, departments have merged but problems were found, so the merger was redone. Prof Attachak Sattayanurak of the Faculty of Humanities said that the merger of departments came after the university became autonomous and the ‘elite’ in the university just saw that there were too many departments in the Faculty of Humanities wasting money, so they pressured the dean who had come by appointment. The merger resulted in delays in academic administration because it was a layered merger. There were still subject programmes, but under new departments, so the chain of command was longer.

‘Eventually there was a proposal that if it was going to be like this, the search for knowledge in each subject would decline, leaving only daily teaching. This led to a new merger, with the group of oriental languages (Thai, Burmese, Pali, Japanese and Chinese) as one department, and the western languages (French, Spanish and German) as another department, but this has not reduced the problems of those subjects. The old problems still remain,’ explained Attachak.

Turning to the so-called open universities like Ramkhamhaeng, which, as a new form of state university, do not limit admissions, they have run into factors forcing them to adapt. One of these is by budget support which the state pays every budget year.

The draft 2019 Budget Act, which passed the first reading in the National Legislative Assembly (NLA) at the beginning of June 2018, shows a budget of 1,194.2 million baht for Ramkhamhaeng University, down from 1,326.6 million baht in 2018, while the budget for the Ministry of Education increases every year.

Hon Prof Wiroj Nakchatri, a teacher in the History Department, Faculty of Humanities, and Deputy Dean for Academic Services, Sisaket Campus, responsible for the campuses in Surin and Sisaket, said that the reduction in budget forced the university to adjust by reducing costs in many ways and there was a move to abolish the Philosophy Department. Even though it has not yet been carried out physically, the importance of the Philosophy Department has declined with its budget allocation reduced from 300,000 baht to 100,000 baht and no additional teaching positions, so that the few teachers have to take on a heavy burden of teaching.

Although philosophy is not a subject that leads directly to a profession, Wiroj insists that it is still necessary to teach because it is a subject that teaches people to know how to think, to differentiate reasons that are correct and false. It teaches how to have a perspective and goals in life, especially in open universities where large numbers of people can learn and complete their studies with fees that are cheaper than other universities.

‘The Humanities “Crisis” and the Future of Literary Studies’ by Paul Jay is a book which Attachak brings up to explain the importance of humanities subjects. Jay believes that in the present era, when budget and the number of people interested in studying the humanities are both going down, humanities scholars and supporters should not just criticise the humanities tide that is being diverted towards practical skills, but should find ways to answer the question of the importance of humanity studies to students, their parents and the administrators of educational institutions both from the perspective of the body of knowledge of the humanities that graduates will receive and the skills that humanities students acquire from the theories that they study or critical methods of education.

Illustration by Nattapon Kaikeaw

Asst Prof Athapol Anunthavorasakul, a teacher in the Faculty of Education, Chulalongkorn University, and Director of the Thai Civic Education Centre, gave the opinion that merely following the demands of the labour market is not a good option and is an excessively rigid goal for the production of graduates because sometimes before you have finished studying, the market has gone.

‘So we have to come back and ask the question why we have universities. If we have them to produce labour, then universities have to be slanted in accordance with the labour market. But if universities are a mechanism to create knowledge for society, then the government must support them. Now the universities are all producing graduates according to the market. But market expectations right now are uncertain because we don’t know if this kind of work will still be there in the next 10-20 years. The labour market changes about every 5 years as well. If we use the labour market as the determiner, there is a very high risk about whether the graduates produced will have guaranteed work. Even more important is that universities must prepare people with a variety of skills ready to face the changing situation of the world and a fast-changing economy.’

In practice Athapol suggests that the universities work proactively with research and private funding sources. Regarding subjects that are academic, they must be maintained. The production of graduates from the humanities also has a high value in the market but it is an investment which does not see short-term gains.

In Thailand there is still a large question mark about whether the humanities really create students with critical thinking, a skill that has been claimed as a trait of education in this field. Attachak, as a humanities teacher, still expresses concern that the aim of the Thai state in producing graduates has not had this objective since the beginning.

‘The conceptual framework of the state emphasises state security and then economic growth was added, which became a force obstructing educational progress in the humanities and social sciences because it blocks and limits the search for knowledge in other dimensions which will help to understand complex social dynamics, so that all that is left is knowledge that helps to maintain state security, such as the study of local history through the study only of local heroes who are on the side of the Thai state, or that emphasises only economic growth.

‘In the past, knowledge in the humanities and social sciences was limited to the elite because it was knowledge that was used to control and command those who were below them. But in the world today, knowledge of this kind has been freed from the hands of the elite and it has become a basic goal how to increase ordinary people’s understanding of the world and society. This new conceptual framework gives people the capacity to think and find their own path in life. It emphasises the greater power of the individual to make decisions and at the same time creates an understanding of a new kind of morality which is needed in today’s world.

It may be necessary to think about policy for the elite to be able to imagine what education would allow people to live together, calmly, peacefully and happily. The emphasis is on the elite first because this minority group is destroying Thai society with the idea that they are the most knowledgeable and clever. But in fact they are the most naïve about social changes,’ Attachak said.

Prachatai English is an independent, non-profit news outlet committed to covering underreported issues in Thailand, especially about democratization and human rights, despite pressure from the authorities. Your support will ensure that we stay a professional media source and be able to meet the challenges and deliver in-depth reporting.

• Simple steps to support Prachatai English

1. Bank transfer to account “โครงการหนังสือพิมพ์อินเทอร์เน็ต ประชาไท” or “Prachatai Online Newspaper” 091-0-21689-4, Krungthai Bank

2. Or, Transfer money via Paypal, to e-mail address: [email protected], please leave a comment on the transaction as “For Prachatai English”