Story by Nutcha Tantivitayapitak

Crew-cuts and earlobe-level haircuts are school rules that seem to have been passed down for so long no one knows their origin. Reading the Thai Rath newspaper dated October 20, 1976, however, tells us that the regulations on students’ haircuts and clothes, as well as on the curriculum content that bans the teaching of political ideologies, even democracy, started after the events of October 6, 1976.

October 6, which seems a distant past, is related to our heads since the time we started to remember things. But how clear is our memory of October 6? We tried short interviews with upper secondary students in several Bangkok schools to find out their perceptions of the incident. More than half of them were unsure and confused it with October 14, 1973. Many have not heard about it at all; some said that they did not learn about it in school, but from the internet, including the Rap Against Dictatorship music video.

We gathered all the textbooks on social studies that we could find and started reading. There were 23, 4 from the 2001 curriculum, 15 from 2008, 2 from 2016, and 2 from 2017. The publishers were Aksorn Charoen Tat ACT Co. Ltd., Watana Panich Publishing Co. Ltd., Aimphan Press Co. Ltd., the Ministry of Education, and even Triam Udom Suksa School which writes its own textbooks. We wanted to find out how much October 6 is mentioned in these textbooks.

How we learn about October 6 in school

The Findings

17 of the textbooks do not mention October 6 at all; some of these were even funnier because they briefly mention October 14 and jump to May 1992, and some omit October 14 and October 6 altogether and tell only about May ’92. 3 textbooks tell the political history of Thailand starting with the Sukhothai period and ending at the change of government system in 1932.

There are 2 textbooks that mention October 6, but only as the name of an event without any description whatsoever.

2 textbooks give about 2-3 paragraphs of brief details of the event; one of these states also that over 100 people lost their lives, which is more than the number recorded in the autopsy reports of the October 6 court case which state that 46 died. They give lèse majesté as the cause of the coup d’état, but nothing about the mock hanging staged by the students that took place before that.

2 textbooks with the same content have the longest text on October 6, referring back to the factors that caused October 14 which is linked to October 6.

Comparison with the October 6 Documentation Project version

We selected the lasr 2 textbooks’ description of 1) the aftermath of October 14, 1973, and 2) the explanation of the communist trend, and compared these texts with the story told by the recently deceased prominent Thai historian, Suthachai Yimprasert, posted on the Oct 6 Documentation website. The contrast is like two different movies with the same title.

The Aftermath of Oct 14 - The Textbook Story

“The situation after the October 14 1973 crisis … the people had more rights and freedom under a democratic form of government. Some students and people exercised their freedom beyond the boundaries, demanding quick changes which were sometimes against the law, that the government could not respond to; some groups made damaging attacks on the government. Conflict arose.”

“Thai political thinking became divisive. In this situation, the majority of the people grew tired of the anti-government protests and the various demands made by different activist groups. People also became disenchanted with the government and the politicians who created disunity and competed for their own interests…”

Many groups were formed; some aimed to help society; some aimed at preserving their own interests, such as student groups, teacher groups, vocational student groups, farmers’ groups, workers and monks. … The movements of some groups were sometimes violent in nature, broke the law and caused trouble for others, such as strikes.

The Aftermath of Oct 14 - The Oct 6 Project Website Story

Under the dictatorship, workers were severely oppressed due to the investment promotion policy that began by the Field Marshal Sarit Thanarat government which aimed at creating a favourable atmosphere for foreign investors by keeping workers’ wages low and at the same time abolishing the Labour Relations law, applying Martial Law to strictly prohibit workers’ strikes; resisting workers could be immediately arrested under the charge of being communist. Thai workers were consequently impoverished and had to work in difficult conditions with low wages and no security for their welfare and working lives.

After the dictatorship regime collapsed as a result of the events of October 14, 1973, a series of workers’ strikes demanding fairness occurred. From just over a month after October 14 to November 30, workers struck 180 times, or 4 strikes a day on average; the strikes spread all over Bangkok and in the provinces. In the following month, there were 300 more strikes at the rate of 10 per day. Many protests by the working class had a great impact, such as that of the port workers that closed down port operations for one day causing the port administration to agree to an adjustment of workers’ wage as demanded. Later on December 12, the railway workers staged a strike, disrupting rail transport, and ending also in an adjustment to workers’ wages.

The problem is whether the strikes were instigated by the left as claimed in National Administrative Reform Council documents. The answer is ‘not likely’, because from the end of 1973 to 1974 when many strikes took place, there was no movement of the left anywhere strong enough to incite thousands of workers to strike. The problem of these strikes was born of the oppressive conditions and impoverishment that had been building up and caused the explosion in that period. It led to the establishment of many workers’ organizations in the form of unions in both state enterprises and private factories. The mobilization of workers into unions could never have happened earlier under the dictatorship.

The Communist Trend - The Textbook Story

“The Students Federation of Thailand began to lose popularity because people perceived that it interfered with the government duties, causing the government to be unable to administer the country smoothly. The parties that suffered losses and the old power groups began to consolidate their base; they tried to rouse a trend for the people to believe that the students were inciting the people to cause unrest. There were constant protests against the government and mob rule in place of the law. In addition, serious accusations were made that the students were communists wanting to overthrow the nation, the religion and the monarchy.”

The Communist Trend - The Oct 6 Project Website Story

After October 14, socialism gradually became the ideology of the student movements in Thailand, and the socialist theory became the weapon that they used to criticize Thai society like never before. According to their critical analysis, Thai society was oppressively class-ridden, and the ruling class had conspired with the American imperialists to severely subjugate the people; the way out of this was to revolutionize the country toward socialism, overthrowing the oppressing class, and building a new society of the proletariat.

The spread of the socialist ideology spurred a great deal of interest among the people. Finally, even the Democrat Party, a large political party with quite a significant role, declared that their governing policies would be “slightly socialist”. Also, 3 new political parties were formed to engage in parliamentary struggle: the Socialist Front Party, the Socialist Party of Thailand, and the New Force Party.

The three socialist-oriented parties gained considerable support from the people as could be seen from the results of the general election in February 1975: 37 candidates from the 3 parties were elected to parliament, 15 from the Socialist Party of Thailand, 12 from the New Force Party, and 10 from the Socialist Front Party. Among those elected, it turned out that Suthi Phuwaphan, an MP from the of Socialist Front Party in Surin Province, received the highest number of votes in the country overall.

The movements of the socialist parties alarmed the ruling elite and the parties of the capitalist class; they became paranoid that these socialist-oriented parties would undermine their own interests and privileges. They therefore tried to attack them with slander to destroy them, such as calling the socialist parties allies of the communists, campaigning against them with the slogan ‘all kinds of socialists are communists’ and accusing them of receiving money from the Soviet KGB, of selling the nation to Vietnam, and being an enemy of the monarchy.

Memories that have long been unchecked

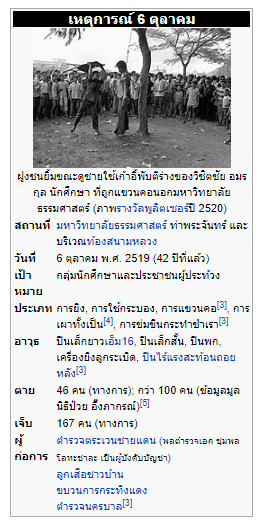

The photograph above is from Wikipedia, the preliminary search resource for people who want to access the story of the morning of October 6, 1976. But this preliminary information is already wrong. The person being hanged here is not Wichitchai Amornkul, second year student of political science, Chulalongkorn University. (His hanging is in another photograph.)

We have been memorizing this for decades, and that is only one example of the mistaken, misshapen memory. It was disclosed only recently that this man was not Wichitchai by the Documentation of Oct 6 Project. If we do not count the website 2519.net that has a collection of the stories of Oct 6 by the Tula Tham Group, but without any progress for many years now, the Documentation of Oct 6 website has a large storage of information that is the most frequently updated at present.

Four decades passed before systematic search and verification

The Documentation of Oct 6 Project began in the year that marked 4 decades after the event. The main initiator is Puangthong Pawakapan, lecturer at the Faculty of Political Science, Chulalongkorn University, and Thongchai Winichakul, former student involved in the event and current lecturer in history at University of Wisconsin, Madison, USA. The main data collectors are Pattaraphon Phoothong, Naruemon Krachangdararat, and Thanaphol Ewsakul.

The project has a website and Facebook page as the main channels for the dissemination of various information, facts, and detailed accounts related to the October 6 event, including photos of news reports from several newspapers during the period of September-October 1976, video and audio footage on the day, and some documents that had never been disclosed before such as autopsy reports and testimonies of state witnesses.

It can be said that this is an archiving type of work.

“When we talk about archives, Thai people can only think of the National Archives which is document storage. Here, it means working with data, storing documents and searching for more, classifying information, carrying out academic research, and presenting the available documents to the public in a way that is easily understandable, for example, making a movie, organizing seminars, or supporting others to conduct October 6 related activities,” Pattaraphon Phoothong explained.

An equally important aspect of this website is the work on “memories”, focusing on interviews with the victims’ family members and close friends and gathering photographs of the event, many of which are still scattered and hidden somewhere.

According to Pattaraphon, “The goal is to introduce the dead to the public so that they know what kind of people they were when alive, what they liked or disliked, what dreams and ideologies they had, why they were involved in the events of that day, and what their families had to face when they died. If these persons were still living, what would their life be like. We ask these questions because we want to point out to people that it was not just a loss of a person, but a loss of a person who could have contributed benefits to society, who had conscience about justice, equality among human-beings. And to get to know the dead is to respect their dignity.”

The sense of guilt and the silence among the survivors

An important question for later generations is why those who were involved in the event themselves have said very little or given very little information about their dead friends; is it because they feel so guilty that they do not want to talk about them?

In his book ‘Oct 6, Unforgettable and Immemorable’, Thongchai Winichakul wrote something interesting about this silence.

“…Though the political situation and the discourse on the Oct 6 massacre had changed, it turned out that both the perpetrators and the victims of incident felt embarrassed and suffered from the wounds in different ways. This has made it difficult for them to demolish the wall of silence that they have built themselves.

“Over 3,000 people, most of them students, had to find refuge by joining the CPT in the hills and jungles. But the CPT and the left movements all collapsed at the beginning of 1980’s. On looking back, in is certain that the CPT had an important role in incubating a more and more uncompromisingly extreme ideology in the students’ movement.

“Most students realized that after the collapse of the CPT, when they were only in their early 20s, they had already lost 2 historical wars: the first was waged in the city ending with the massacre of their friends; the next was a war in the hills and jungles ending with a loss of faith. How could they not be disgusted with themselves, feeling humiliated, and ashamed of the catastrophic mistakes they had made? And then they had to plead for mercy from the state which they had earlier despised. Several chose to commit suicide.

“The fact that the sacrifice was viewed at that time as contribution toward noble ideals is not weighty enough to counterbalance the other fact that if those friends had survived that Wednesday morning, they would have another chance in life just as the living from the former left do today. Hence, the massacre is not a subject that the former left can discuss without reflecting back to the moral dilemma that has been plaguing their minds…”

This may be part of the answer why details about the deceased began to be compiled only in 1996, when a commemorative event was organized for the 20th anniversary.

History detectives going back through time looking for the relatives

‘Time’ seems to be the key enemy of data collection after 40 years; where should the team start?

The researchers obtained the addresses and telephone numbers of relatives from the autopsy reports, and sent a letter to or called each of them. Sometimes they were lucky to find someone that offered help to look for the relatives or friends of the deceased.

Some former October 6 students gave suggestions for over 10 names. Out of the 36 letters sent to the addresses on the autopsy reports, 4 people called back; many of the letters were returned by the post office. Certainly after 40 years some of the houses are no longer there.

The first relative that called was the older sister of a law student at Ramkhamhaeng University who died; the letter was sent to her old home that has been rented out to a tenant. The first words she uttered was “Why contact us only now?”.

The second caller lived in Phetchaburi; this relative recounted that he/she studied at Ramkhamhaeng University with the deceased and knew what happened to the person, but did not want to be interviewed. He/she later suggested the team contact an older sister. The older sister did not want to say anything and told the team to talk to the younger sister. The answer they received from the younger sister was that she did not wish to talk about this, nor to be contacted again.

“She said something like ‘Do not bother trying to persuade me; you don’t know what our family has gone through’. We think perhaps after the event, several people may have cursed the family for being communist, or the police may have gone to their house; fear may have caused the family to disengage themselves from the whole affair,” Pattaraphon recounted.

Photographs from a saleng recycling man

Sets of photographs came from various sources.

Frank Lombard, former reporter of Radio New Zealand currently living in Thailand, met Pattaraphon through an introduction from a neighbour.

A large set of photographs that belongs to Pathomporn Srimantha contain photos taken at several of the sites. The team obtained the set because a friend reported that Pathomporn had them. Pathomporn is interested in political history and has acquired several sets of related document and photographs; this particular set was bought from an antique shop which had in turn bought it from the owner of a saleng [recycling tricycle]. From the angle of the camera, these photographs must have been taken from the side of the state officials.

“We ran into things we have never seen before; that is why we enjoy our work, acting like detectives.”, said Pattaraphon.

Irregularities in the autopsy reports

“Our country has a lot more documents that have never been publicized which reflect state violence; we need to continue our search,” Pattaraphon emphasized.

Information cover-up seems to have been normal practice for the state from the past to the present. The autopsy reports show traces of this as well. For example, each form should contain information about the person retrieving the body and about witnesses, or give more information about the body in question, but they do not. The cause of death was simply put as being hit by shrapnel without indication whether this meant that explosives were being used; there was no information about what types of bullets cause the wounds even though examining bullets could indicate the type of firearms used.

In addition, in comparing the reports issued by Siriraj Hospital with those by the Police Hospital, it was found that the latter contain no description of the body at all, while the Siriraj Hospital reports give physical details such as a male, curly hair, medium build, dark complexion, wearing such and such coloured shirt and trousers, including even the contact details of the person retrieving the body which has led the team to find the name of an additional person that was hanged.

What cannot be retrieved, disposal of documents older than 25 years

“I think there were more than 70 bodies.”, said a police officer involved in October 6 documentation while talking ‘off the record’ with a researcher.

Looking up the number of deaths during the event, the website states 41 students and people and 5 officers and people on the right wing, but this officer still insisted “I think it should be more than that.” When asked for evidence, however, he replied “I don’t know of any, it may have been destroyed already.”

Exactly the same thing happened at Siriraj Hospital, which kept all documents for 25 years, then disposed them off according to a Prime Minister’s Office Regulation, B.E. 2526. Fortunately, documents on October 6 were among those transferred to the Museum of the Attorney-General. Nonetheless, documents related to incidents that occurred on dates other than October 6 were not included in this set, such as the hanging of 2 electricians in Nakhon Pathom; these had already been destroyed.

The Poh Teck Tung Foundation and Ruam Katanyu Foundation both assisted in transporting the dead and injured to hospital. The researchers had the opportunity to interview 2 Ruam Katanyu staff who took part in taking bodies to the Institute of Forensic Medicine; both asked to remain anonymous out of safety concerns. They insisted that the Foundation vehicle would not be able to leave the scene without the permits being signed off by the police, and therefore there must have been records of how many corpses and how many injured persons were picked up on the day.

Foundation staff also took photographs of the injured, the dead, and several scenes of the incident which could show the scale of violence being perpetrated that is useful for anthropological or historical research. Unfortunately, they had all been disposed of because the Ruam Katanyu Foundation had to move its office from Khlong Toei to the Bang Phli area.

At the Poh Teck Tung Foundation, there are also documents relating to their work on October 6 because records have to be kept about the unknown corpses they pick up. But the Foundation refused to give access to the researcher because she was not a relative of the dead. They also see the project as political and “don’t want to be involved in politics”.

Nonetheless, information from interviews of several witnesses increased the researchers’ curiosity more and more. This prompted Pattaraphon to examine all photographs and footage in detail, placing them next to each other for comparison, and finally coming out with a new finding that the total number of persons hanged is (at least) 5, not 2 as believed at the beginning. (Read here)

The need to understand the perpetrators too

Whether we count the officers and the right-wingers who lost their lives as victims or not, the researcher’s personal opinion is that the memories of those on the right and the junior officers should also be studied in order to understand the situation that made them decide to kill.

She believes that without understanding their stories, we would never be able to understand the violence shown on that day; she thinks a study of the perpetrators can be done, but they will not be categorized as victims.

A further question may be whether the study can create ‘the ability to understand’ their action. As an answer, Pattaraphon cited the example of an interview with a member of the Red Gaur Group that was at the scene.

“He said he regretted what had passed and his eyes welled up while saying ‘I didn’t behave well; I wasn’t a good person. I feel sorry about it to this day. Afterward, I got ordained as a monk and I have been living my life without harming anyone again.’

“When you hear words like these, people on the victims’ side may feel angry, and think that by publicizing the experience of the perpetrators we are making excuses for their horrific acts in the past. We cannot control the readers’ feelings, but we only want to explain that people can change after 40 years. With such change, how do we deal with it?

“What we are interested in are the conditions, circumstances and situations that make people choose to act one way or another, or to resort to violence. We think that creating this kind of understanding can lead to the prevention of violence,” said Pattaraphon.

Prachatai English is an independent, non-profit news outlet committed to covering underreported issues in Thailand, especially about democratization and human rights, despite pressure from the authorities. Your support will ensure that we stay a professional media source and be able to meet the challenges and deliver in-depth reporting.

• Simple steps to support Prachatai English

1. Bank transfer to account “โครงการหนังสือพิมพ์อินเทอร์เน็ต ประชาไท” or “Prachatai Online Newspaper” 091-0-21689-4, Krungthai Bank

2. Or, Transfer money via Paypal, to e-mail address: [email protected], please leave a comment on the transaction as “For Prachatai English”