At 5 pm on 7 December 2020, King Vajiralongkorn presided over the opening ceremony of the new Supreme Court building along with Queen Suthida. The event looked just like other royal ceremonies in Thailand. The king lit candles, knelt before a statue of the Buddha, then pressed an electronic button to open a ceremonial curtain in front of the building. The King and the Queen were received by 120 officials and deputies of the Supreme Court.

Notable among them was Methinee Chalothorn, the new President of the Supreme Court, who in September last year became the first woman ever to be appointed to this position. She made a donation of money to the King. King Vajiralongkorn and Queen Suthida then entered the renovated building. Now in a black judicial gown, the King gave a speech to the judicial officials. It was televised on every channel in Thailand at 8.00 pm. In his speech, the King asked the judges to do their job well so that people have faith in the system. The ceremony in itself might have been another superficiality. But the renovation of the building was another example of royal consolidation under new reign.

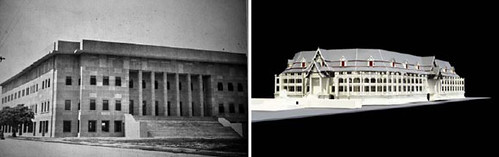

The original Supreme Court building was constructed by Khana Ratsadon in 1939 to celebrate the end of extraterritoriality. It had a modern look. Six pillars at the front of the building symbolized the six values of the politico-bureaucrat group which overthrew the absolute monarchy in 1932 - one of which was independence. To eradicate the largely already forgotten Khana Ratsadon’s legacy of the time, a legacy now revived thanks to the protesters, the renovation which began in 2013 superimposed a Thai-style gable on the building.

The renovation is part of a wider process of expunging the memory of the 1932 revolution. In 2017, the plaque embedded in the road in front of King Chulalongkorn’s statue marking the People’s Party takeover of power disappeared in unexplained circumstances. The statues of Khana Ratsadon members Plaek Phibunsongkhram and Phraya Phahonphonphayuhasena (Phot Phaholyothin) were removed last January, when Fort Phibulsonggram was renamed Fort Sirikit, and Fort Phaholyothin was renamed Fort Bhumibol in March. On 24th June last year, when the Thai democratic opposition held events to commemorate the 1932 democratic revolution, Gen Apirat Kongsompong, the army chief at the time, held a ceremony to celebrate the Boworadet rebellion, a failed royalist attempt to overthrow the People’s Party and return Thailand to the absolute monarchy.

Left: The old Supreme Court Building

Right: The new Supreme Court Building

Source: 2475article

The timing of the Supreme Court event was interesting. The renovation of the building was finished in January 2019. Then President of the Supreme Court Slaikate Wattanapan had held an opening ceremony before the judges moved in. The royal opening ceremony may have been delayed because King Vajiralongkorn spent most of his time in Germany before he returned to Thailand in October. But the royal ceremony might also have been timely in light of potential dissatisfaction with the establishment growing within the judicial branch.

Resistance within the judiciary, unlike other institutions, is difficult to detect. Sometimes, it is disguised by extreme formality, but sometimes it is explosive. Thais often called the judiciary “daen sonthaya” or “twilight zone”, hinting that something mysterious, complicated and unpleasant is going on. But Thais cannot be very vocal against the judiciary without risking prosecution for contempt of court. A series of military coups has come and gone, but the Thai judiciary has been largely left untouched. Most of the time, the putschists would simply ask the judicial branch to continue as before while they took over the executive and legislative branches.

In October 2019, the judiciary came under the spotlight after judge Khanakorn Pianchana shot himself in protest against interference in his court’s decision from his superiors in favour of military officers in the south of Thailand. In a 25-page verdict, he also mentioned the work environment and job insecurity of judges and meddling in court decisions, a practice which was enabled by the 2017 Constitution. After he recovered from his wounds, he was prosecuted for violating the gun law. He shot himself again, this time fatally, in March 2020 to protest against the establishment. Seminars and vigils were held to call for judicial reform along with other political issues.

Meanwhile, dissatisfaction with the government was growing due to the questionable election in 2019, the dissolution of the Future Forward Party in early 2020, and corruption scandals throughout 2020. As the protesters started gathering on the streets in June, the judiciary became part of the frontline institutions in dealing with the protesters. Signs of the judicial resistance could be seen here and there.

In August, the Criminal Court ordered the unconditional release of 9 activists. Anon Nampa, a human rights activist, said that court criticized the police for their excessive behaviour against the protesters. In October, the courts dismissed the government’s request to close media outlets covering the protests including Voice TV, the Reporter, the Standard and Prachatai. In a separate Facebook post in December, Anon said that he had received words of encouragement from many judges behind the scenes in the past 3-4 months.

Throughout 2020, we also saw the dismissal of many court cases against anti-coup politicians and activists from 2014-2019. The cases against Worachet Pakeerut for not reporting to the authorities after the military coup were dismissed when the Constitutional Court deemed the junta’s order unconstitutional. Chaturon Chaisang was acquitted of sedition charges after speaking out against the military putsch in 2014. Nine activists who called for elections were also acquitted of sedition charges.

These cases might be seen as the calm before the storm as the courts clear up old cases to prepare for the upcoming lèse majesté cases. It could also be seen as a compromise to minimize public criticism or internal conflict in the judiciary.

Another possible point of conflict is Methinee Chalothorn. After she was appointed President of the Supreme Court in September last year, pictures circulated on the internet showing her at a PDRC protest which led to the military coup in 2014. The ultraroyalist group now has many of its members in the cabinet or organizing yellow shirt protests.

In the opening ceremony of the Supreme Court building, Methinee donated money to the King (a practice which pro-democracy protesters want to abolish). A group claiming to be “anonymous judges” spread the information with the assistance of Jaran Ditapichai, a political activist in exile and former National Human Rights Commissioner, accusing Methinee of ordering courts to deny bail to pro-democracy protesters and collecting money from courts which she could donate to appease the King in the hope of getting a seat on the Privy Council.

Left: Official portrait of Methinee Chalothorn

Right: Methinee Chalothorn at a PDRC protest

Source: Bright TV

The anonymous judges group also claimed that Sitisak Vanachakij, Presiding Justice of the Supreme Court, gave a lecture in November for new judges coming to work in the Supreme Court, the content of which was mostly criticism of protesters for being manipulated by democratic politicians. Several judges walked out in protest. Sitisak denied the accusation, saying that the lecture dealt only with guidelines for treating protesters with dignity and respect, including avoidance of unnecessary detention orders.

Prachatai tried to contact Jaran Ditapichai for a possible interview with one of the judges for more information but received no response.

During the protests in 2020, the courageous individuals within conservative institutions have spoken out against unjust orders. In June, Sgt Narongchai Intharakawi exposed fraud in the military regarding allowance payments. In October, the Washington Post reported that police were increasingly reluctant to crack down on protesters. In the same month, a group of dissatisfied civil servants opened a Facebook page under the name “Free Thai Civil Servant” to expose unpleasant practices within the Thai bureaucracy. The page now has more than 18,000 subscribers. In November, a retired ambassador also opened the Facebook page “the Alternative Ambassador” to express criticism of the current government. The page now has more than 110,000 subscribers.

While resistance in some institutions is clearly visible, the same cannot be said of the judiciary. The “twilight zone” remains as mysterious as ever, but Thais cannot help but ask whether something surreptitious is going on in there.

Prachatai English is an independent, non-profit news outlet committed to covering underreported issues in Thailand, especially about democratization and human rights, despite pressure from the authorities. Your support will ensure that we stay a professional media source and be able to meet the challenges and deliver in-depth reporting.

• Simple steps to support Prachatai English

1. Bank transfer to account “โครงการหนังสือพิมพ์อินเทอร์เน็ต ประชาไท” or “Prachatai Online Newspaper” 091-0-21689-4, Krungthai Bank

2. Or, Transfer money via Paypal, to e-mail address: [email protected], please leave a comment on the transaction as “For Prachatai English”