During the 2020 - 2021 pro-democracy protests, reporters in the field have been arrested and injured despite wearing visible press IDs and staying in groups with other reporters, while reporters covering resource disputes, development projects, and labour rights continue to face lawsuits.

Meanwhile, reporters working in the Deep South are at risk of harassments, arbitrary detention. Their sources are also threatened to pressure reporters to stop covering stories.

In many cases, assaulting reporters is normalized, such as when Prime Minister Gen Prayut Chan-o-cha sprayed hand sanitizer onto reporters at the Government House, or when Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Defence Gen Prawit Wongsuwan appeared to punch a reporter, which was explained as him 'teasing' the reporter.

Often, violence against Thai journalists are not investigated, and no perpetrators are brought to justice. On the occasion of the International Day to End Impunity for Crimes against Journalists, Prachatai presents a report on the threats faced by journalists in Thailand and the impact of such threat on the journalists themselves and on communication rights.

Crowd control police pulling on a reporter covering a protest (Photo from iLaw)

Press freedom situation in Thailand

In the aftermath of the National Council of Peace and Order (NCPO) coup of 22 May 2014, Freedom House ranked Thailand’s media as “Not Free” for a number of years running. Following the general election in 2019, the country’s status was briefly raised to “Partly Free” only to return again to “Not Free” the next year.

In their 2020 annual report, Freedom House explained that Thailand’s improved ranking in 2019 was due to the fact that although laws limiting press freedom were is still in use, the NCPO canceled some of the controls that left Thai and foreign-language mass media exposed to junta censorship, threats and lawsuits.

In the same report, Freedom House also mentioned the case of a Belgium reporter who was taken from his residence after trying to interview a political activist who was assaulted prior the election, as well as the case of a Voice TV reporter who was sentenced to prison by the Court of First Instance for a Twitter post on labour rights abuse at a local chicken farm.

Explaining the ranking downgrade in its 2021 report, Freedom House stated that Gen Prayuth Chan-ocha’s government had declared a state of emergency using a 2005 Royal Decree on Public Administration in Emergency Situations, which gives the government power to limit mass media reporting. At the same time, it also imposed a Computer Crimes Act which threatens the possibility of lawsuits and stipulates that violators can be sentenced up to 5 years in prison. The report further noted government requests for deletion of content, the arrest of reporters covering anti-government protests and government appeals to the courts resulting in the closure of at least 4 news agencies.

According to Reporters without Borders (RSF)'s 2021 World Press Freedom Index, the 2019 election did not result in any significant improvement in press freedom in Thailand. Government critics continued to be stifled by strict laws and a politically-compromised judiciary.

RSF also discussed the 2019 Cyber Security Act, which increases governmental authority and poses a threat to online data, and the use of lese majeste laws under Section 112 of the Criminal Code which stipulates 3-15 years of imprisonment as tools to block the public and mass media from expressing opposition to the government.

As a consequence, media coverage of the the pro-democracy protests in 2020 met with considerable self-censorship and demands for monarchy reform were systematically deleted from mainstream mass media reports

The Thai government continues to use the COVID-19 pandemic to enact laws prohibiting the reporting of false information and news likely to cause public concern. They have also arrested or repatriated reporters and bloggers from Cambodia, China and Vietnam who took refuge in Thailand back to their respective countries to face imprisonment.

According to the UNESCO observatory of killed journalists, no reporter has been killed in in Thailand since 2013. Two journalists lost their lives while covering military crackdown on the protsts in 2010. However, the perpetrators were never apprehended. Three other cases have no investigation information.

Defining violence towards mass media

Phansasiri Kurarb, a lecturer at the Faculty of Communication Arts, Chulalongkorn University and a scholar of journalism in conflict settings, says that mass media work is directly related to violence; journalists are on the frontline, discovering truths, posing questions, and investigating events that arise in society – in many instances, violent events that endanger their lives and mental health, and threaten the safety and survival of their respective organisations.

Phansasiri added that the risks stem from interacting with people to collect information in dangerous settings: at demonstrations; in armed conflicts; during civil unrest; in war; terrorism; pandemics; disasters, and when investigating the misuse of power by state or other private beneficiaries. Data collected by the Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) indicates that more journalists die from reporting on politics, corruption and human rights than from covering war news.

According to Phansasiri, the reports of various human rights groups and international organisation about violence directed at mass media lend support to a theory proposed by Johan Galtung, a Peace Studies scholar, who categorises such violence into 3 levels, as follows:

1. Direct/physical violence - an obvious and direct threat to life which can involve threats, physical assault, inflicting pain or illness, sexual harassment, kidnapping, detention, and ultimately murder.

2. Structural violence - legal mechanisms, regulations, and market structures that impede the work and freedom of mass media. Phasansiri gave four examples of structural violence, as follows:

- Legal measures which are vague or unfair; for example, lawsuits, orders, announcements or measures obstructing communication rights, press freedom, rights to access information, or freedom of expression, such as threatening to file charges for revealing false information or a government news bill which stipulates penalties for mass media.

- Overseeing/monitoring mechanisms which are vague and unfair, authorising licenses, investigating, giving penalties, limiting access to opportunities, censoring content before and after publishing, and favoritism, such as denying access to membership in a media profession organisation.

- Market structures that hinder free competition and the presentation of diverse content, such as:

- Awarding radio frequencies for state profit as opposed to public benefits and communication rights, effectively ending community radio and leaving most other public communications channels in the hands of state agencies: the military’s Channel TV5HD and its (MUX) network; the Public Relations Department, state enterprises such as MCOT Public Company and public media such as Thai PBS. According to Phansasiri, things are not really different from the past when the state monopolised broadcasting frequency, a big step backwards for media structure reform.

- High entry barriers for the industry. A large amount of capital is needed to maintain a media business. And there is an algorithm bias that requires platform providers to focus on engagement numbers, which encourages the dissemination of false information to obtain profit from advertisement. Content production is also not always transparent.

- Organisational mechanisms that do not support the welfare rights of workers: constraints on labour unions in negotiating labour rights: affirming freedom of expression while working behind closed doors; lobbying to protect private benefits and not freedom of expression.

3. Cultural violence - undemocratic thought processes that do not conform to human rights principles, impeding the work of authorised organisations, directors and media workers; and a society that does not support mass media to work freely, such as:

- Beliefs and understandings in society about what should not be said or asked without deviating from proper morals, peace and order; beliefs which often conflict with internationally accepted values of a democratic society promoting equality, human rights, and the concept of global citizenry. Local examples include issues related to the monarchy, religion, and nation-state (Buddhism-royal nationalism). When the media poses questions concerning such issues, they will be labelled as nation-haters and anti-royalists who want to overthrow the throne, as happened to Thapanee Eadsricha who was attacked for not loving the nation and loving outsiders more than her fellow nationals after writing sympathetic reports about Rohingya boat people seeking asylum.

- The attitudes of people in government and state agencies who believe the mass media questions and investigations are antagonistic towards the state. Donald Trump, former President of the United States of America, is a good example, as our is own PM’s ferocious responses and refusal to answer questions … lecturing the mass media on the importance of cooperating with the state, etc.

- Conservative organisational culture. For example, understandings of proprietary control, seniority, and patriarchy – one must be a strong woman who lives like a man to receive support. One also has to overlook sexual harassment issues and set aside gender sensitivity. And then there are class divisions between central and local reporters and stringers who are treated like hired help, not shareholders in news, get little welfare protection in consequence.

High pressure water, teargas, rubber bullets, arrests, assaults, fireworks: mass media becomes the target of protest violence

Mob Data Thailand collects data on public protests in the country. From 2020 to 29 October 2021, there have been at least 1,291 protests, some 58 of which were suppressed. During these protests, at least 5 mass media workers were arrested. Some 14 people reported being shot by rubber bullets. At least 3 people were physically assaulted. At least 4 were injured by explosive devices. Those arrested and injured all wore symbols indicating that they worked for mass media. Most were harmed while standing together, separate from the protestors.

Using weapons to suppress protests first started on 15 October 2020, when the government declared an emergency situation. Officers used high pressure water trucks and tear gas as weapons to disperse the protesters. On 16 October 2020, Kitti Pantapak, a Prachatai journalist, was detained while live-streaming the situation. His wrists were tied behind his back with cable ties for more than 2 hours. He was charged with disobeying a lawful order and released. Other reporters in the area were affected physically by the tear gas, which caused skin and respiratory system irritation. The protest suppression did not conform to international law.

Prachatai reporter Kitti Pantapak was arrested while covering police dispersal of the 16 October 2020 protest

From then until now, officers have continued to use weapons to suppress protests and violence has escalated. Rubber bullets were used for the first time at the 17 November 2020 protest in front of the parliament. The state started to forcefully arresting protestors at the 13 February 2021 protest in front of the city pillar shrine. Other escalations include:

- Using force over five hours to suppress a protest, and arresting over 100 people including reporters.

- According to several photographers at the 17 November 2020 demonstration in front of parliament, police were the ones who triggered a confrontation with the protesters.

- At the 13 February 2021 protest, volunteer nurses and shooting vocational college guards were assaulted, as reported by “Ratsadon” leaders at the end of the protest

At the 16 January 2021 protest, when protesters gathered at the Samyan Intersection to demand the release of activists arrested while writing on banners at the Democracy Monument, crowd control police surrounded the area to disperse the protesters. There was an explosion in front of Chamchuri Square and Tanakorn Wongpanya, a reported for The Standard, was injured on his left thigh.

In addition to Kitti, Bancha (last name withheld), a Naewna reporter, was arrested while on duty covering the 28 February 2021 protest near the residence of Prime Minister Gen Prayuth Chan-ocha.

Bancha said in an interview with Thai Lawyers for Human Rights that officers ran over and detained him, pushing him to the ground. He was kicked and hit by batons, before being handcuffed with cable ties. Despite identifying himself as a mass media worker, Bancha was charged for violating Section 9 of the Royal Decree on Public Administration in Emergency Situations, the Communicable Diseases Act, for gathering and using force, causing chaos in society, fighting and obstructing lawful officers and harming officers. If found guilty he could face 5 years in prison.At a protest at Sanam Luang on 20 April 2021, which called for limits on the King’s authority, three reporters, 2 of whom were women, were shot with rubber bullets while on duty near Khao San Road. Those injured were Channel 8 reporter Phanittnat Phrombangkoet, who was shot in the head causing brain inflammation and had to stay in an intensive care unit for 1 night; Prachatai reporter Sarayut Tangprasert , who was shot by 2 bullets in his back; and Thanyalak Wannakot, who was shot in her leg. All three had symbols identifying them as media workers.

Prachatai reporter Sarayut Tangprasert was shot in the back with a rubber bullet while covering the 20 April 2021 protest

During the 18 July 2021 protest, members of the activist group Free Youth marched from the Democracy Monument to the Government House. Officers arranged a line to block the march at the Phan Fa Lilat Intersection, where Plus Seven reporter Thanaphon Koengphaibun, who was clearly identified as a journalist, was shot in the hip while standing with other reporters. There were no warnings from authorities. 2 other reporters were also shot by rubber bullets: Matichon TV reporter Pheeraphong Phongnat, a Matichon TV reporter was shot on his left arm, and The Matter photographer Channarong Ueaudomchot, a photographer was also shot on his left arm.

At the 10 August 2021 protest, independent protestors started to gather at the Din Daeng intersection with the goal of calling for the Prime Minister to resign. They later became known as the “Thalugaz” group. On that day, The Reporters founder and reporter Thapanee Eadsrichai was shot by a rubber bullet on her leg. Independent photographer. The Human Rights Lawyer Alliance stated that at least 2 mass media workers were harmed with rubber bullets that day.

During a protest at the Victory Monument on 11 August 2021, Laila Tahe, who conributed photos to Benarnews and Rice Media Thailand, was hit by a police officer with a baton, which missed her arm but damaged her camera lens.

The damage to Laila Tahe's camera after she was hit by a police officer while covering the 11 August 2021 protest

At least 3 mass media workers were shot by rubber bullets during the 13 August 2021 protest. Phichitpak Kaennakam, a VoiceTV reporter, was shot near his knee. He said in an interview with Matichon Online that he was shot while standing together with more than 10 other reporters to hide from the rain. All were wearing mass media armbands. However, the police approached and shot at them, even after they tried show their credentials, holding up armbands and showing their cameras or camera stands. Phichitsak said that another female photographer was also shot in the leg.

At the 15 August 2021 protest, at least 2 mass media workers were shot with rubber bullets. Khao Sod Online reported that a VoiceTV reporter was shot in the legs.

At the 21 August 2021 protest, Thapanee Eadsrichai reported that a journalist with The Reporters was hit with great force on the right side of his helmet by an object while live reporting from the Din Daeng intersection. He fell to the ground and was later treated for a torn eardrum, requiring three months of rest and observation.

At the 29 August 2021 protest at the Din Daeng intersection, Nation reporter Suphachai Phetthewi was shot by a rubber bullet near the back of his right ear. Siam Rath reported that fireworks were shot towards a group of reporters, injuring Chatanan Chataphiwan in his right hand and bruising Nation photographer Woraphong Noithaptim's right hand.

Thai Lawyers for Human Rights reported that at least 5 mass media workers were injured during the protest suppression at the Din Daeng intersection on 13 September 2021. Almost 20 reporters were targeted by lasers before rubber bullets were shot from the Army Band headquarters. They were standing on the opposite side of the protesters.

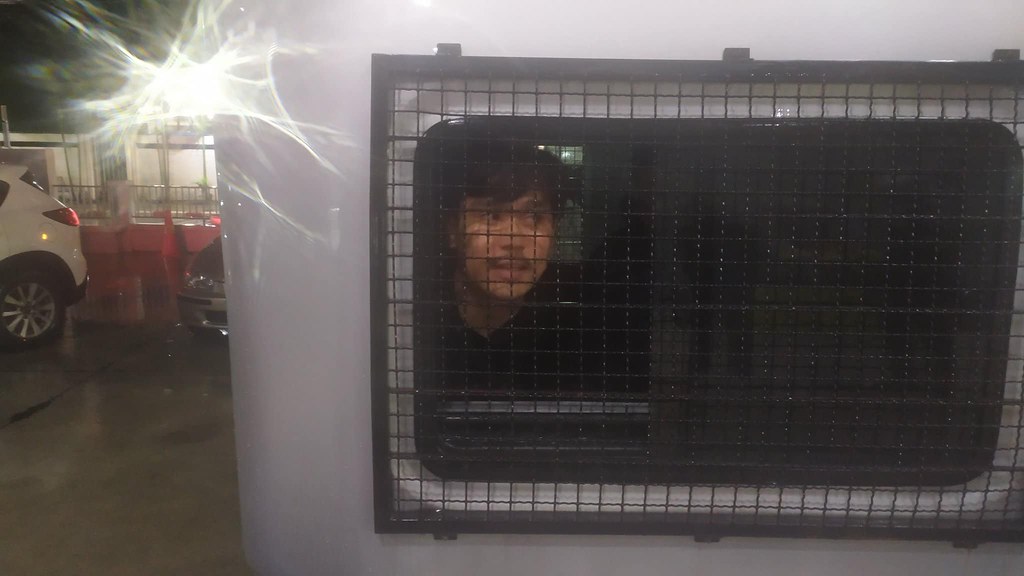

During the 13 September 2021 protest, the police also arrested Natthapong Mali, a reporter from Ratsadon News, and another woman citizen reporter from the Free Our Friends Facebook page for violating the Emergency Decree while they were live streaming from the Din Daeng Intersection. Both had their hands tied up with cable ties.

Ratsadon News reporter Natthapong Mali was arrested while covering the 13 September 2021 protest

At the 27 September 2021 protest, a woman reporter from the Kathoei Mae Luk On Facebook page was pushed by the police. They also tried to arrest her, but she was rescued by a civilian.

At the 28 September 2021 protest, Natthanon Charoenchai, a journalist with The Reporters, said he was shot with high-pressure water cannon until he fell while reporting on the situation at the Nang Loeng Intersection. At the time, he was standing close to 10 other reporters who were also live-streaming.

At the 6 October 2021 protest, “Admin Ninja”, an independent reporter from the Live Real Facebook page, was arrested while live-streaming the situation at the Din Daeng intersection despite having clear press identification.

At a protest on 29 October 2021 held in memory of Warit Somnoi, a 15-year-old boy who died as the result of being shot in front of the Din Daeng police station, there were reports that police shot rubber bullets from a moving truck towards protesters and journalists on the footpath. iLaw reported that police seized a mobile phone from a civilian reporter affiliated with the Kathoei Mae Luk On Facebook page.

The police tried to seize a mobile phon from a civilian reporter from the Kathoei Mae Luk On Facebook page. (Photo from iLaw)

Three reporters - Sarayut Tangprasert, Thanaphong Koengphaibun, and Channarong Ueaudomchot - filed a lawsuit with the Civil Court, asking for protection for mass media workers. To this day, the Civil Court has yet to summon concerned parties for investigation. It also dismissed Sarayut’s case on the grounds that the Court was unable to prohibit protest suppressions as the Royal Thai Police had to investigate any unlawful actions to prevent threats towards mass media workers.

Focus on lawsuits. Reporting news in conflicts situations: resources, development projects, labour rights and SLAPPs

When it comes to conflicts involving resource disputes, development projects, and labour rights, there is limited record of physical violence. Since the 2019 general election, threats against journalists have taken the form of lawsuits for published pieces.

There have been cases where threats caused reporters to feel unsafe. For example, journalists were threatened while covering a public hearing for a mine concession in Khlong Yai subdistrict, Tamot district, Phatthalung province. Manager Online reported that Channel 7 reporter Isana Udomsilp and Thai PBS reporter Latda Manirat, a Thai PBS reporter, along with the teams from Thairath TV and Amarin TV, were followed by a car while taking photos of water sources in the area. A man who claimed to be representing the company seeking the concession then came to ask them if they were reporters, and prohibited them from coveirng the hearing. He also followed them in car until they left the area.

Meanwhile, the Human Rights Lawyers Association has been collecting data on at least 195 cases of strategic lawsuits against public participation (SLAPPs) in Thailand, at least 10 of which were against journalists.

Since 2019, at least 3 cases were against journalists: a chicken farm defamation lawsuit against Voice TV reporter; a contempt of court case against Sarinee Achavanuntakul and the Krungthep Turakij newspaper editor; and a defamation lawsuit filed by a Thai mining company in Myanmar against former Green News editor Prach Ruchiwanarom.

Suchanee Cloitre (Photo from iLaw)

In the chicken farm defamation case, former Voice TV reporter Suchanee Cloitre was sued for tweeting about a court ruling in a case brought by a Myanmar worker against the Thammakaset company. The court ordered the farm owner to pay the worker on 14 September 2017.

On 16 November 2017, Chanchai Phermphon filed a complaint with the police at Koktum Police Station in Lopburi, but the public prosecutor dismissed the case on the ground that the defendant only intended to report on the court ruling as a journalist and did not intend to cause damage to the Thammakaset company.

On 1 March 2019, Thammakaset company authorised Chanchai to file charges against Suchani again with the Lopburi Provincial Court. On 24 December 2019, the Court of First Instance sentenced Suchanee to 2 years in prison for defamation, since the words she used were not the same as the court ruling, causing damage to Thammakasets reputation.

The Court of Appeal dismissed the case on 23 October 2020 on the grounds that, as a journalist, Suchanee has received information from directly interviewing the Myanmar worker. Although her words were not the same as the court ruling, it attracted readers. The words were also used by foreign media, and offered in good faith. Currently the case is before the Supreme Court.

Sarinee Achavanuntakul

Another case started in August 2019. Writer Sarinee Achavanuntakul and Krungthep Turakij editor Yutthana Nuancharas were charged with contempt of court for an article published in Krungthep Turakij newspaper on 14 November 2019. The article discussed the disqualification of potential MP candidates using the objective to produce mass media as stated on the memorandum of association as a reason, even though the candidate's company does not run a media outlet.

The case concluded in October 2019 with a public apology from Sarinee, who retracted the inappropriate wording she used to criticize the ruling of the Supreme Court's Election Case Division from her article.

Prach Ruchiwanaram

The most recent case is that of the defamation lawsuit filed by the Myanmar Pongpipat Company, a Thai mining company in Myanmar, against Prach Ruchiwanaram, then editor of Green News for reporting that a Myanmar court ordered the firm to pay Tawai villagers 2.4 million baht for tin mine environmental damage. The report was published on the Green News website on 13 January 2020. The case is currently at the attorney stage.

This case is the second time that the mining company has pressed charges against Prach. In 2017, the company filed a lawsuit for defamation and reporting false information in response to the article “Thai mine destroys Myanmar water sources” which was published by the Nation Online. The case ended with mediation and the company dropping the charge.

Reporting from the Southern Border Provinces

The current phase of unrest in the Southern Border Provinces started in 2004. Phansasiri, Thai Media for Democracy Alliance (DemAll) coordinator Nattharavut Muangsuk, and independent reporter Naulnoi Thammasathien, all of whom has experience in reporting in the Deep South provinces, said that journalists in the region are not a target of violence like they are in protests, but may become collateral damage.

Nevertheless, Nualnoi said that, although journalists in the Deep South are not a target of violence and do not get arrested as often as those who cover the protests, threats against press freedom are still a cause for concern.

On 24 November 2019, officers of unknown affiliation raided a coffee shop in the Talat Kao area, Yala province, and detained Wartani news agency's editor-in-chief and 4 other employees: Ruslan Musor, Mapakri Late, Fais, and Weera Mateha.

Wartani editor-in-chief Ruslan Musor said that, during an editorial team meeting preparing to cover an attack on a village security booth at Lamphaya subdistrict in Yala at the coffee shop, more than 10 cars of officers came to search the place, claiming that there was a suspect there. Police officers asked to see Ruslan’s identification card, claimed that they had been trying to find him for a long time, and announced that they would be taking him in. Seven people were detained.

Ruslan was taken to Yala police station for interrogation, without a lawyer. Officers tried to collect DNA samples but he refused. Additionally, the officers seized his mobile phone to check his IMEI number, claiming that they just wanted to collect information and look at his Facebook and LINE messages, before releasing him. They also repeatedly told Ruslan to explain to others that it was all a misunderstanding.

Ruslan said that Wartani reporters have always been threatened, sometimes with lawsuits. They also get followed while traveling. Officers visited family members or summoned them to ask them to tone down their reporting. Other than threatening the reporters and their families, officers also visited their sources at home to pressure Wartani into removing articles or prohibit them from speaking to Wartani.

Mass media workers harmed by new source so often it almost appears normal

Reporters assigned to the Government House are another group that faces physical violence. In 2019, photos of Thai PBS reporter Wasana Nanuam being punched in the stomach by Gen Prawit Wongsuwan, Deputy Prime Minister and Minister of Defence, appeared in the press.

Wasana later explained that they were just playing around. In her words, “…it’s normal to tease or prank reporters that ask a lot of questions, particularly reporters covering the military. They grit their teeth and hit our shoulders, arms and stomach. It seems normal now.”

In January 2021, Amarin TV reporter Naphat Praniphon had his microphone taken, hit on the shoulder, and placed in a neck lock while interviewing Chaiphon ‘Uncle Phon’ Wipha, a suspect in the case of a girl who went missing and later found dead in Koktun subdistrict, Dongluang district, Mukdahan province.

On 9 March 2021, Gen Prayut sprayed alcohol hand sanitizer at reporters from many agencies after being asked about plans to adjust his Council of Ministers. In addition, while the Head of the NCPO, Gen Prayuth threw banana peels, water, instant noodles packets, and a tuberculosis test kit at reporters. There are also photos of him hitting reporters on the head.

On 3 September 2021, photos were published of Gen Prawit using his hand to touch the face of a reporter in anger and using his fist to punch at the face of a female reporter after being asked about conflicts within the Palang Pracharath Party, of which Gen Prawit is currently head.

The impact of violence

According to Phansasiri, the use of various types of violence against people working in mass media threatens public communication rights. Instead of hearing from all sides, people will only receive partial truths. They will be left without a space to exchange ideas, discuss matters and debate issues in order to reach a conclusion or agreement. Especially during conflicts and crises, society needs a complete understand of the truth and public discussion to resolve conflicts and move forward without leaving anyone behind. When constraints have been placed on the media, the people lose power over their own fate as well as the means to speak to those who possess power.

In keeping with the above, Nualnoi added that the violence which effects people working in mass media often starts from little things that grow bigger over time, becoming a new standard, a new normal.

“If what happened at Din Daeng is repeated again and again, we’ll get a new normal that says whenever there is a protest, say a protest at Ratchadamnoen, officers will announce that the area off limits, that the media is not allowed inside. This means the eyes of the public will not see some places, some points. And we’ll accept this as the New normal,” Nualnoi said.

Nattharavut expressed concern about the safety of people working in mass media, especially the independents. He noted that independent journalists often report on issues that mainstream media does not dare to report. As a result, they face greater risk from state authorities and third parties who disagree with protest demands.

In addition to the obvious physical risks to to journalists, the DemAll coordinator noted the psychological impacts they faced. He added that many reporters have developed PTSD as a result of the stressful conditions they operate in, waking up in the morning to report on protests that turn violent with water cannon, rubber bullets, firecrackers, fireworks, and explosions, not knowing if they will be hit by firecrackers or lose a limb to a rubber bullet.

“Fear and worry eat at our hearts, but we can’t do anything because resignation means no work. Moving within the mass media industry is not easy to do. We have to endure and continue. If an agency has a good editorial team, we can talk and the editor will listen. Some may find a way to change teams and not go out to face that problem, but for the most part, that’s the minority,” Nattharavut said.

Proposals to end violence against mass media workers

Phansasiri believes that adherence to democratic principles and the protection and guarantee of equal rights for the people, especially communication rights which cover information access, freedom of expression and public gatherings, are the factors required to end violence against journalists.

When violence is committed against mass media, every sector should have a proper investigation process to uncover the truth establish responsibility and assure that the perpetrators are really punished. Protection mechanisms should also be in place to protect victims physical and mentally.

The Faculty of Communication Arts professor offered the following proposals for concerned parties:

1. Government, state agencies and overseeing agencies should implement policies and laws to protect the right to freedom of expression, to promote diversity in mass media and fair competition. They should also provide training to governmental agents, the general public and journalists to promote understanding of the role each must play in protecting the rights and freedoms of the people and reducing the risk of violence. In addition, the government, state agencies and overseeing agencies should avoid all levels of violence and never accept violence as a legitimate recourse.

2. The legislative sector should work on amending laws that potentially threaten public freedoms. It should also provide a public space where people can freely present facts as well as discuss and debate issues in order to resolve conflicts peacefully.

3. Media groups and media professional organisations should uphold freedom of the press and freedom of the people. They should also work to understand different types of violence and ways that organisations can prevent violence. For instance, trainings can be organized and information disseminated information on how to avoid promoting violence in the researching and news reporting process. The organisations should also ensure the labour rights and welfare of all workers.

In addition, mass media groups and media professional organisations should draw up a response plan to prevent violence and provide their personnel with protective equipment. When violence does occur, efforts should be made to immediately report it to every sector, including the public.

4. Mass media platform providers should cooperate with mass media organisations to ensure mass media communication access and quality. They should also promote free and fair public communication. Guidelines should be used to timely monitor content that might lead to violence against the people and journalists. Journalists’ privacy should also be protected.

5. The public and the civil sectors should work together to help people understand the connection between freedom of the people and freedom of the press, protecting mass media organisations and freedom of speech for the people. They should also point out that violence is unacceptable even when used is retaliation. Violence should be the last resort.

Nattharavut suggested that the most urgent action is to educate society, to help society mature and acknowledge the growing popularity of new media. At the same time mass media organisations need to take proactive measure to protect reporters in the field. For example, there should be a war room to keep track of protest situations and issue immediate reports. Field coordinators are also needed. When any problem occurs, coordinators could contact officers and protestors. This would allow reporters to present problems in a timely manner, seeing events as they unfold, not just finding footage afterwards.

In addition, the DemAll coordinator encouraged media professional organisations to be brave enough to present their demands to the state and engage in symbolic actions when the government has limited their freedom, such as banning or not reporting news, setting up the camera without a reporter, or having reporters wear body armour to signify that they are in a war. At the same time, journalists were encouraged to develop themselves, increase their awareness and be more wary of state domination.

Natthaphong Mali from Rasatdon News proposed that online mass media and independent news agencies should be given formal recognition. Profession organisations, the Thai government and people should realise that the world is changing. News agencies are no longer just the main TV channels and newspapers. The world is now online and borderless. Anyone can be in mass media, provided they maintain principles and ethics, reporting the situation accurately.

Noting the deteriorating level of mutual trust in society Nualnoi suggested that those working in mass media clearly announce that they are journalists as soon as they enter dangerous or complex areas. She also proposed that journalists don’t work alone but enter the site with a partner who can help to look out for trouble.

“Journalists don’t have any weapons. To guarantee their own safety journalists must rely on little more than their sincerity, their transparency and their work,” said Nualnoi.

Prachatai English is an independent, non-profit news outlet committed to covering underreported issues in Thailand, especially about democratization and human rights, despite pressure from the authorities. Your support will ensure that we stay a professional media source and be able to meet the challenges and deliver in-depth reporting.

• Simple steps to support Prachatai English

1. Bank transfer to account “โครงการหนังสือพิมพ์อินเทอร์เน็ต ประชาไท” or “Prachatai Online Newspaper” 091-0-21689-4, Krungthai Bank

2. Or, Transfer money via Paypal, to e-mail address: [email protected], please leave a comment on the transaction as “For Prachatai English”