A large number of sex crimes in Thailand go unreported every year, in part because there are simply not enough female police officers, discouraging many victims from speaking up in the first place.

As Thailand marked International Women’s Day this week, a group of policewomen renewed their effort to solve the problem. They face an uphill battle against prejudice, apathy and sheer bureaucratic intransigence.

An undated photo of policewomen on a parade. Image: @kp.police.cadet / Facebook.

The reports are horrifying. In one, a 12-year-old girl who suffered years of abuse was compelled to secretly film the perpetrator assaulting her yet again to present as evidence; she reported the crime earlier but the police did not believe her.

In another, a man took his young granddaughter to a Saraburi police station to report that she had been abused by her stepfather only to be shooed away because he was not her biological parent.

And in Samut Sakhon, a girl who took refuge with her aunt after allegedly being raped by an influential figure in the province was summoned to a police station at the insistence of the man accused of perpetrating the crime.

These tales, told recently at a seminar marking 2022 International Women’s Day, share a common theme: all of the investigating officers were male. In truth, there is little likelihood that sexual assault victims will be questioned by female officers because there are so few of them. By one estimate, the entire police command fields only 500 of them, in a country of nearly 70 million people.

Rights advocates say that the lack of female inquiry officers deters many victims from reporting crimes, and that those who do often face insensitive treatment, or outright apathy, from the male-dominated police force. A major reform is long overdue but police brass don’t appear to take the matter seriously, said a retired policewoman who spent decades spearheading calls for change.

“I’ve been trying to change things for a long time now, but have yet to succeed,” Police Colonel Chatkaew Vanchawee, a former senior inquiry officer in Bangkok, said in an interview on Friday. “I think it’s up to the people in charge. Many people think of sexual crimes as a ‘domestic matter,’ or they treat it as an unimportant issue.”

Police Col Chatkaew Vanchawee. Image: Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung / Facebook.

Chatkaew is chairperson of the Female Inquiry Officers Club. As the name suggests, it’s a group for the few women working as police inquiry officers, who play a critically-important role in police investigation efforts. For years, Chatkaew and her group have been calling for an increase in the number of female inquiry officers and an overhaul of the way sexual assaults are reported and investigated.

According to Chatkaew “prejudice and attitudes keep change from happening.”

The Boys in Brown

Inquiry officers, investigators in English, are often the first point of contact for crime victims in Thailand. They ‘inquire’ about the nature of the crime, the time and place it transpired, and establish the sequence of events. They also gather information on perpetrators and determine the injuries and damages suffered by victims.

In addition to collecting evidence, they decide whether a charge can be pursued, apply for warrants, arraign suspects, and write case reports for prosecutors.

Nearly all of them are male. Official police data indicates that there are about 10,000 inquiry officer positions around the country. Only 700 are women. The actual number is even smaller, Col Chatkaew said, since inquiry officers are sometimes transferred to other postings, a common practice in the police force.

Col Chatkaew estimates that there are only about 500 female inquiry officers stationed nationwide on any given day. By way of comparison, in 2013 Thailand had a total of around 2,000 surgeons, a profession that is considered to be one of the most severely understaffed.

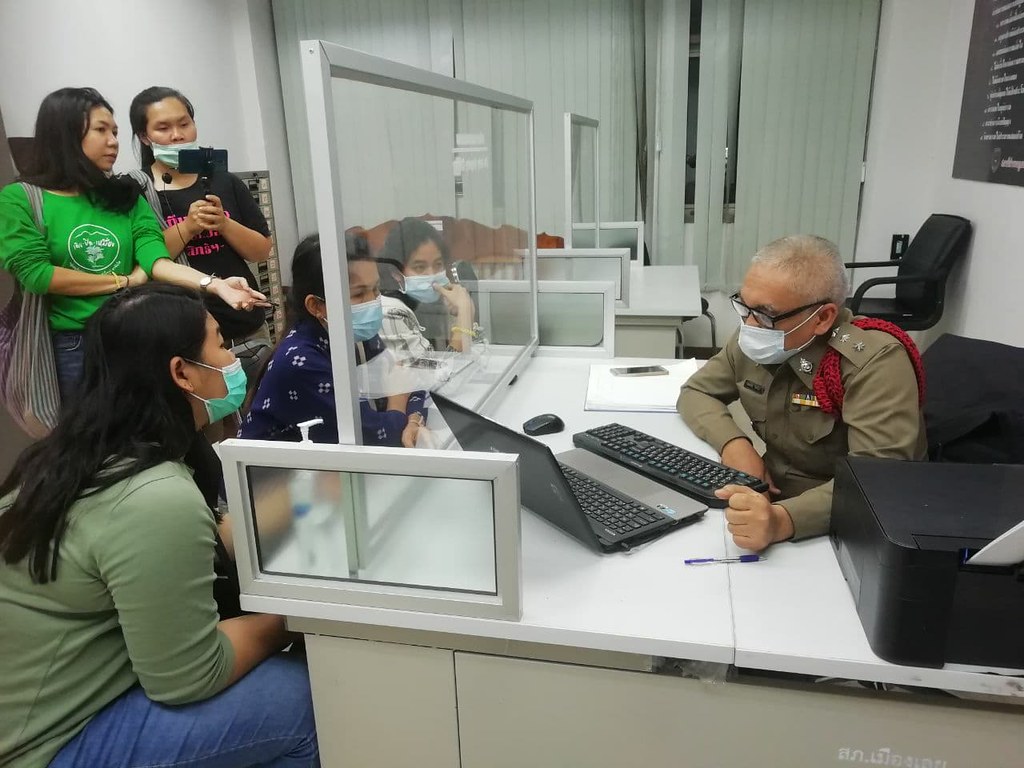

A policeman questions a group of environment activists who say they were followed and harassed by security officers in Loei province on 4 February 2021. LINK

As Col Chatkaew points out, this means that women who wish to report a sexual assault will probably have to talk with a male police officer, who may or may not treat the complaint with due sensitivity.

“It’s different, talking with men, and talking with women,” Col Chatkaew said. “When women are questioned by women, they don’t get embarrassed. They’re more comfortable speaking out and providing details.”

Under Thai law, women have the option to be questioned by a female officer; if a request is made, it must be honoured.

But in practice, the process of finding a female inquiry officer can be long and complicated. First, the inquiry officer in charge must inform the station superintendent about the request. Then, it is forwarded to the regional commander, who contacts other superintendents in the area to see if any female officers are available.

Once an officer is found, the regional commander will have to sign a special order designating her as the inquiry officer for the woman who made the request.

Because of the time involved, many women end up foregoing the request and settle with giving their testimony to male officers.

A culture of indifference

Thailand only introduced female inquiry officers in 1995. The first group consisted of only 15 policewomen. Chatkaew was one of the 15. She worked in the investigation field until her retirement two years ago.

Col Chatkaew has personally known many male inquiry officers who “understand the victims’ feelings and respect their dignity.” But anecdotes of policemen dismissing or downplaying sexual crimes are quite common.

Some of these stories were recounted to a horrified audience at a March 5 seminar by Panadda Wongphudee, a celebrity actress who also runs a charity that assists victims of sexual abuse.

At the conference, which was organized by the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung foundation, Panadda said that over the course of her 10 years of philanthropy, she has personally witnessed many cases of police mishandling of complaints from women and children.

In a particularly extreme case which took place in a location close to Khao Kho National Park, a 12-year-old girl who had been repeatedly raped by a grocery store owner alerted the police, only to be told that she lacked evidence.

Knowing she would be assaulted again, the girl asked a friend to hide nearby and film the incident.

“Would she have to resort to this, if the police just listened to her in the first place?” Panadda asked.

She also noted another case in Songkhla, where a group of young women filed assault charges en masse against a famous modeling agent. According to Panadda, although the victims were from different provinces across the southern region the police told all of them to travel to a station in Songkhla to file charges and testify. No support was given for their travel expenses.

“Sometimes I wonder why it is so hard to catch the perpetrators in each case. And why,” she continued, “is it so exhausting [for the victims]? Why do victims have to fight this much? Why did that kid have to film herself? Why do children have to fight for themselves like that? When will sexual crimes get the serious attention they deserve?”

There is also a lack of privacy and consideration for women in general. Many police stations don’t have a private room dedicated to questioning sexual assault victims.

“Some women have had to file complaints about sexual crimes while sitting next to drug suspects, or when many people were around them at the police station,” Panadda said. “Who has the courage for that? It’s already difficult enough to say, ‘I was raped.’ Some women only report incidences days later because they lack the courage. They were not certain of what kind of policemen they would have to deal with.”

“This is something I’ve seen for a long time and keep seeing again. No change at all,” she added.

According to Anchana Heemmina, a women’s rights activist based in Yala province, the problem is even worse in the southern border provinces in communities where Islamic law is practiced.

When an assault occurs, police sometimes let community leaders negotiate with the perpetrator and the victim so that the matter can be “settled” without launching a formal criminal investigation.

“In using social customs to resolve the dispute, the police are employing a system that wasn’t designed by women, one where women have no participatory role,” Anchana said at the conference. “Decisions are based on social rules, not the law, and without consideration for consequences to women’s lives.”

A very active post

One reason hiring additional female inquiry officers is a big challenge is because it’s already one of the least desirable jobs in the police hierarchy thanks to a massive workload.

Policemen salute as their commanders walked by during the rank bestowing ceremony on 1 February 2022. (Credit: Thai Police's Public Affairs Division)

The math is staggering. A typical police station may have only several inquiry officers on hand, each of them working an 8-hour shift. They receive dozens of criminal reports and complaints each day. Many officers spend much of their shift questioning crime victims and contacting relevant authorities, working through the backlog of paperwork in their ‘free time’ before repeating the same cycle again the following day.

“Barely anyone wants to take the job. It’s very exhausting,” Col Chatkaew said. “For other officers in a station, once their shift is over, they go home. It’s not like that for inquiry officers. They have to fill in the paperwork even if their shift is over. It's like having homework all the time.”

According to the Royal Thai Police, hundreds of inquiry officers ask to be transferred to other positions each year, a testament to the job’s unpopularity. Col Chatkaew said many officers will pull whatever strings they have to avoid being posted as an inquiry officer.

It’s also known internally as the job with one of the highest suicide rates. The immense stress that comes with the post takes its toll on mental health, experts say. In a span of 10 months in 2019, six inquiry officers took their own lives. In 2020, there were seven suicides. The latest known suicide of an inquiry officer was in November 2021.

So it’s no surprise that inquiry officers are either idealists or people who don’t have a choice.

“We also have a shortage of male officers,” Col Chatkaew said. “There aren’t enough of them, yet more crimes are being reported every day, and crimes are getting more complex every day.”

Phone holders

The police command can’t just simply hire more women. Only officers with advanced knowledge and proven career records are eligible for the position of inquiry officer, and many women on the force have not yet been given a chance to rise that far in the first place.

Instead, female officers are often tasked with relatively junior roles, serving as secretaries and aides to senior policemen. When they do get media attention, it’s mostly because of their appearance.

This was the case for Patarasaya ‘Viking’ Rerkrut, a young policewoman whose only role at a major news conference in August 2021 was to hold a mobile phone for Police Commissioner Suwat Jangyodsuk so he could question a suspect remotely.

“All netizens want to know more about this policewoman, who the person behind the face mask is, because her loveliness can be felt even through the face mask!” exclaimed the author of an article on one Thai news site.

Police Captain Patarasaya Rerkrut holds a mobile phone for Police Commissioner Suwat Jangyodsuk on 26 August 2021. Image: Youtube/Bright TV

“It comes from the misperception that women aren’t as good at something as men,” Col Chatkaew said. “Many commanders assume female officers are only capable of handling insignificant matters. Since they don’t get assigned important work, they can’t advance in their careers.”

Reports of how many female officers are enlisted in the police force vary but it is clear that they are a tiny minority: somewhere between 4 to 7 percent of the 200,000-strong rank and file.

In yet another blow to gender representation in the police force, the Royal Police Cadet Academy announced in 2018 it would stop taking new female applicants.

Critics say the decision is counterproductive, undermining efforts to increase the number of policewomen, but police officials maintain that women can still join the force through other means, applying with a relevant university degree and taking part in mandatory training courses.

Putting the right women in the right job

At any rate, raising the number of female inquiry officers alone may not solve the problem entirely. According to Col Chatkaew, the long term solution is to set up a task force in every major city and region of Thailand specifically to handle sexual crimes.

Col Chatkaew envisions a force comprised of police, legal experts, and social workers. Highly-motivated and well-trained women and men, they would question victims, investigate crimes, and work with multiple organisations - shelter homes, hospitals, and mental health therapists - to help rehabilitate victims.

“Many inquiry officers want to do something else anyway. They want more glamorous jobs with pretty photo-ops, like making drug busts. And women who want to work in this position often can’t because they haven't advanced far enough in their careers,” she said.

A group of female inquiry officers wait to receive awards for their distinguished work at the Police Club in Bangkok on 5 January 2021. Image: Female Inquiry Officer Club.

“We need opportunities for female officers to grow. Let them have the chance to help children and women.”

In the meantime, the Female Inquiry Officers Club organises workshops for the handful of female inquiry officers currently on the force, teaching them psychology and other skills necessary for working with victims of child abuse. To fund these courses, the group sometimes has to rely on contributions from international rights organisations.

The club also pairs retired or senior female officers with younger ones, in order to pass on and share experiences.

“We need people who have passion and understanding to work in this job,” Col Chatkaew said.

Since 2007, Prachatai English has been covering underreported issues in Thailand, especially about democratization and human rights, despite the risk and pressure from the law and the authorities. However, with only 2 full-time reporters and increasing annual operating costs, keeping our work going is a challenge. Your support will ensure we stay a professional media source and be able to expand our team to meet the challenges and deliver timely and in-depth reporting.

• Simple steps to support Prachatai English

1. Bank transfer to account “โครงการหนังสือพิมพ์อินเทอร์เน็ต ประชาไท” or “Prachatai Online Newspaper” 091-0-21689-4, Krungthai Bank

2. Or, Transfer money via Paypal, to e-mail address: [email protected], please leave a comment on the transaction as “For Prachatai English”