Back in 2003, Thailand ratified the 1966 UN International Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination (CERD), though it does not recognize the competence of the relevant Committee under Article 14 of the Convention regarding an individual complaints mechanism. In 2011, Thailand submitted its Country Report for the first through third reporting cycles (2003-2008). This report is a mandatory read for anyone interested in any of Thailand's ethnic communities and is available here. However, this official version lacks the tables, which are, nonetheless, available here in an advance unedited copy. The main difference appears to be in the paragraph numbering.

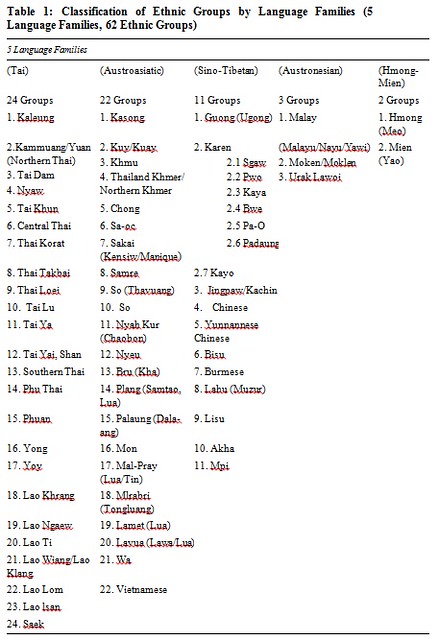

What is truly remarkable is the diversity of ethnic communities recognized in the Country Report. Sixty-two ethnic communities are recognized, including the Central Thais, using a scientific classification scheme rooted in ethnolinguistics and developed by the Research Institute for Languages and Cultures of Asia at Mahidol University as part of their Ethnolinguistic Maps of Thailand project (Map available from this column and here). The full list of ethnic communities recognized can be seen in this figure:

What is also extraordinary is that the Country Report recognizes ethnic groups which have not officially existed for over one hundred years, most interestingly the Lao of Isan (Northeastern Thailand) and the Malay of the Deep South. The reason these groups ‘disappeared’ is closely linked to nation building during the late nineteenth century, in the case of the Lao including the integration of large parts of the Lao states of Champassak and Vientiane on the Khorat Plateau into the Kingdom of Thailand via the Thesaphiban reforms. For example, the two monthon (‘circles’) which included the word ‘Lao’, Lao Kao and Lao Phuan, lost their ‘Lao’ label and became instead Isan (meaning northeast in Sanskrit) and Udon (meaning north in Sanskrit) under the Thesaphiban administrative reforms of Prince Damrong Rajanubhab, as reflected in the 1897 Local Administration Act.

At a second level, there was a disappearance of the Lao from officialdom, most visible in the official censuses. This was a reaction to the internal re-organizations as well as to Western race theory and the problem of French colonialism, which took the stance that all of Siam’s tributary states, especially the Lao and Cambodian ones, were up for grabs, a stance it enforced in the Pak Nam Incident and the 1893 Franco-Siamese War. Almost everyone from what is now known as the Tai-Kadai ethnolinguistic family became ‘Thai’ during this period in terms of their ‘race’, according to Thai censuses, beginning with the 1904 census. In a broadly parallel process, the Thai Malay, though actually from the Austronesian language family and quite clearly not so related to the Thai in terms of customs or religion, also disappeared, with the invented ethnonym ‘Thai Muslim’ coming to replace the name ‘Malay’ in an attempt to suppress any attempt to link Thai Malay culture with the culture of those in Malaysia. Historically-speaking, this was an understandable decision at a time when communism was rising and both the borders and stability of the ‘new nations’ of the postcolonial era were still somewhat fluid.

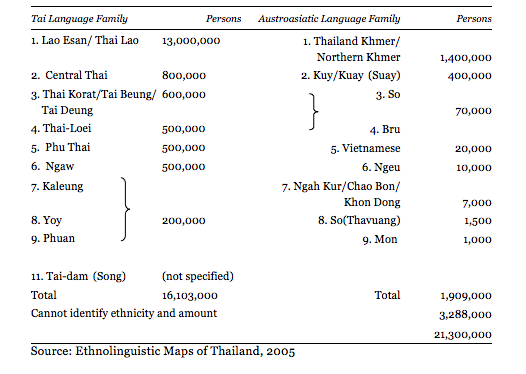

This disappearance of the Lao and Malay was confirmed by Thai ultra-nationalism under the first Phibun Songkhram administration of 1938 to 1944, when the country of Siam was renamed Thailand and ‘Thai’ became both a country adjective and a nationality, with even the concept of regional divisions of Thais such as ‘Isan Thai’ being outlawed by the 12 Cultural Mandates. By the Sarit administration, this renaming exercise was mainly complete, though the concept of Isan did re-emerge as an ethnonym inclusive of all the ethnic communities of the Northeast. And, just to make sure we are really talking about the Lao of the Northeast rather than another group which might be called “Lao Isan”, here is a picture reproduced from the Country Report as described in another column on the subject of the re-emergence of the Lao first published at The Isaan Record, here:

As can be seen in this table, there are 13 million Lao in the Northeast, with another 500,000 being labelled Thai Loei, though the language of the Loei ethnic community is, in fact, a dialect of Lao, that of the Luang Prabang subfamily. Furthermore, Thai Khorat is arguably a creole of Thai and Lao. In addition, there are a further 3.288 million in the table whose ethnicity is not identified, many of whom could be partially Lao. Thus, we have an ethnic minority which is around 15 million strong in the Northeast, the majority of whom are, quite accurately and in line with the scientific consensus, labelled ‘Lao’.

That Thailand has recognized the Lao and the Malay (not to mention the Northern Khmer) to the international community is probably one of the most progressive decisions of His Majesty’s Royal Thai Government over the past decade. The problem was no-one told the Lao because within Thailand, the Lao are still not officially recognized, nor do they even have an ethnic association one could inform, unlike the Chinese ethnic associations of Thailand. In addition, no-one seems to have told the Malay, either. In fact, Thailand does not formally recognize the Lao or Malay within Thailand. This is even emphasized in paragraph 44 of the Country Report: “Thailand has no policy or law that divides its people by class, race or nationality under the democratic system and in Thai society.”

Thus, the Thai Malay and Thai Lao exist in a quantum state.

In fact, almost all the ethnic communities in the Country Report, except for very small ethnic communities, such as the ten highland peoples of the North and west who have been officially recognized due to their problematic status since the days of the Tribal Research Institute, exist in such a state. The reason why recognizing the Lao, Malay, and for that matter the Northern Khmer is especially important is that these ethnic communities have their own states: the People’s Democratic Republic of Laos, Malaysia, and Cambodia. Thus, on the eve of the integration of the Asean Economic Community, this highly progressive recognition of Thailand’s wide variety of ethnic communities should be celebrated as a major step forwards in terms of ASEAN relations and potentially fruitful social and economic transboundary effects.

But only if it can be materialized through national legislation, such as the draft National Language Policy.

2016 will be important because this year, Thailand will report again to the CERD Committee. Thailand is unusual in having an almost blanket reservation on implementing legislation in agreement with the CERD, contained in Article 4. In 2012, the Committee, in dialogue with the Thai delegation, in 2012 raised a number of issues, including its very broad reservation to Article 4. Article 4 reads:

States Parties condemn all propaganda and all organizations which are based on ideas or theories of superiority of one race or group of persons of one colour or ethnic origin [my emphasis], or which attempt to justify or promote racial hatred and discrimination in any form, and undertake to adopt immediate and positive measures designed to eradicate all incitement to, or acts of, such discrimination No. 9464 220 United Nations — Treaty Series 1969 and, to this end, with due regard to the principles embodied in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the rights expressly set forth in article 5 of this Convention, inter alia:

(a) Shall declare an offence punishable by law all dissemination of ideas based on racial superiority or hatred, incitement to racial discrimination, as well as all acts of violence or incitement to such acts against any race or group of persons of another colour or ethnic origin, and also the provision of any assistance to racist activities, including the financing thereof;

(b) Shall declare illegal and prohibit organizations, and also organized and all other propaganda activities, which promote and incite racial discrimination, and shall recognize participation in such organizations or activities as an offence punishable by law;

(c) Shall not permit public authorities or public institutions, national or local, to promote or incite racial discrimination.

Thailand’s reservation reads as follows:

The Kingdom of Thailand interprets Article 4 of the Convention as requiring a party to the Convention to adopt measures in the fields covered by subparagraphs (a), (b) and (c) of that article only where it is considered that the need arises to enact such legislation.

During the committee’s considerations, this reservation was described as being “so broad that the Committee could not tell which obligations the State party was prepared to accept”; moreover, the nature of this reservation has been formally objected to by multiple other state parties, namely France, Germany, Romania, Sweden, and the UK.

This year, Thailand will have a choice about what to do regarding the ethnic communities which disappeared as a reaction to decades of systemic socio-political and cultural processes involving colonialism, imperialism, and forms of fascism. It will either make progress with its human rights as regards ethnic communities, in cooperation with the Committee responsible for CERD, and raise its reservation regarding Article 4, or it will have to explain to the international community what the problem is.

However, as the CERD does accept shadow reports from civil society and the National Human Rights Commission of Thailand (which did file a shadow report last time, as did the highland peoples), the voices of those larger ethnic communities who have re-appeared may also be heard. When that happens, the quantum nature of Thailand’s larger ethnic communities will start to collapse, which, if managed properly, will be a great opportunity.

Prachatai English is an independent, non-profit news outlet committed to covering underreported issues in Thailand, especially about democratization and human rights, despite pressure from the authorities. Your support will ensure that we stay a professional media source and be able to meet the challenges and deliver in-depth reporting.

• Simple steps to support Prachatai English

1. Bank transfer to account “โครงการหนังสือพิมพ์อินเทอร์เน็ต ประชาไท” or “Prachatai Online Newspaper” 091-0-21689-4, Krungthai Bank

2. Or, Transfer money via Paypal, to e-mail address: [email protected], please leave a comment on the transaction as “For Prachatai English”